The Protection from Internet Falsehood and Manipulation Bill 2019, otherwise known as theSocial Media Bill, has a provision that will empower the Nigerian government to unilaterally order the shutdown of the internet if passed into law.

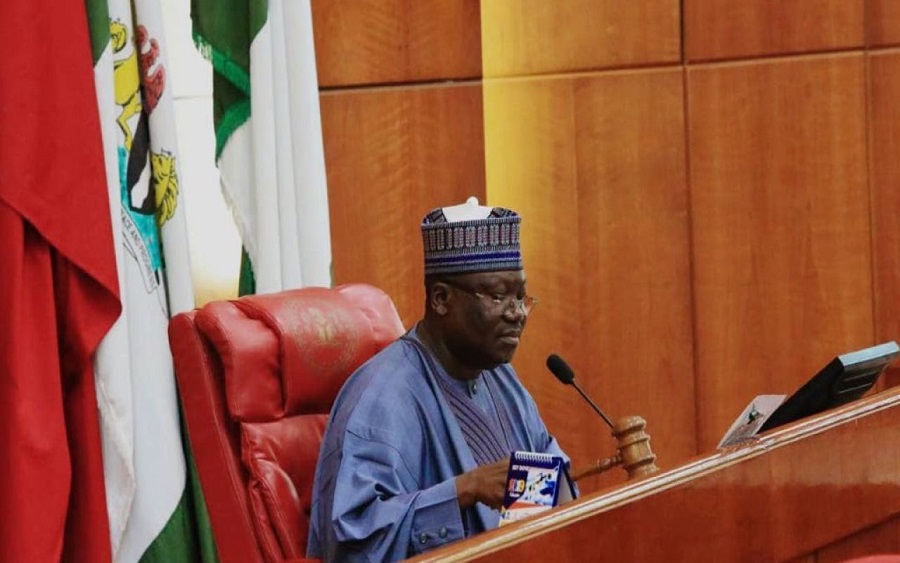

The bill, being pushed by Senator Muhammad Sani Musa (APC-Niger East), passed the second reading this week.

The Nigerian government, disposed to regulating social media, said such regulation is necessary in the interest of “our national peace and unity.”

Critics said the bill is designed to clamp down on freedom of speech.

“We have sufficient cause to believe that this Bill contains elements that may affect the right to free expression of internet users in Nigeria and we intend to follow up on it as it goes through the legislative process and is officially gazetted,” Paradigm Initiative Nigeria said in a statement.

A similar bill that prescribes a death penalty for “hate speech” is also before Nigerian lawmakers.

The Social Media Bill may have an easy passage since the country’s National Assembly is controlled by the party at the centre – the All Progressives Congress.

President Buhari told Nigeria in October that his government will take “decisive action” against persons who spread hate speech on social media.

Although he said the government respects the rights of individuals, Buhari said abuse of technology that undermines national security will not be allowed to fester.

“Whilst we uphold the constitutional rights of our people to freedom of expression and association, where the purported exercise of these rights infringes on the rights of other citizens or threatens to undermine our national security, we will take firm and decisive action,” Buhari said in his Independence Day broadcast on October 1.

Part 3 (12) of the bill gives law enforcement agencies the power to shut down access to the internet and social media without recourse to the National Assembly or a court.

The section says: Law Enforcement Department may direct the NCC to order the internet access provider to take reasonable steps to disable access by end-users in Nigeria to the online location (called in this Clause an access blocking order), and NCC must give the internet access provider an access blocking order (emphasis ours).

An internet service provider that refuses to obey the order on conviction by a court may be fined N10 million for each day the order is not obeyed.Another section of the bill prescribes a fine of ₦300,000 or three-year jail term or both for anyone found guilty of making statements that “diminish public confidence in the performance of any duty or function, or in the exercise of any power of the Government.”

Nebulous provisions, according to critics of the bill, portend danger to journalists and for freedom of speech.

“This is nothing but self-preservation by the powers that be in Nigeria to muzzle free speech and ban dissent,” Aanu Adeoye, managing editor at TechCabal wrote on Twitter on Friday. “The senators you elected suddenly don’t want to be accountable to you or anyone else.”

If passed into law, Nigeria may join the unenviable league of African countries where internet blackout has been used to stifle voices of opposition and to control narratives.

Controlling the narrative

Just before DR Congo went to the polls to elect a new leader on December 30, 2018, there was an internet blackout. When the results trickled in on December 31, major cities, including the capital city Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, were without internet connection.

Two major internet service providers in the country said they shut down the service on government orders.

The Congolese authorities said the action was taken to curb circulation of fake election results and forestall “popular uprising”.

But the executive director of Paris-based Internet Without Borders Julie Owono said internet blackout, as seen in some African countries, is synonymous with irregularities.

“Past experiences in Mali, Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea have proved that internet disruptions during elections are clear signs of irregularities,” Owono said.

Cameroon, Chad, Tanzania and Uganda have all limited access to the internet and digital media at different times.

Despots’ tactics

Some of the countries where the internet has been shut down since 2015 now have presidents that have turned the leadership of their countries to their chattels.

66-year-old Idriss Déby has been the president of Chad since 1990. Before a new president was sworn in this year, Congo was ruled by Joseph Kabila between 2001 and 2019. Before then, his father led the country between 1997 and 2000 when he was assassinated.

Omar Al-Bashir was only ousted in April in a coup that was preceded by massive protests against the government. Before his ouster, he was the leader of Sudan for almost 30 years.

Cameroon’s Paul Biya has been the country’s president for nearly 37 years.

THE GUARDIAN