It was an historic moment for the Korean peninsula. On February 10, 2018, the official Twitter feed of the Olympic Games posted a photo of the International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach stood on an ice rink behind twenty or so women, hockey sticks in hands, helmets pulled down and serious looks on their faces. On their jerseys, the outline of the entire Korean peninsula and one word: ‘Korea’.

It’s only sport, some might say. But it was a momentous political gesture. The two Koreas, North and South, were about to take to the rink as a unified team. They would be comprehensively beaten by Switzerland that night and again by Sweden and Japan in their next two matches. But that was of secondary importance.

“The team is coming together,” said Bach after the loss to the Swiss. “Everything is coming together and hopefully it will stay together and everybody will respect this Olympic truce resolution [of the United Nations] and show here that these Games should be beyond political tensions.”

Beyond? It was a strange word to choose. Nothing, ever, is beyond politics. Especially when it comes to international sport. The unification of the two Koreas hockey teams was a deeply political act. A positive one, certainly, and one that was endorsed by Bach and his IOC cronies. But to say that it was beyond politics is either naïve or willfully oblivious.

But in the light of last week’s furor surrounding the IOC and its reiteration of the ban on political demonstration at the Olympic Games, it is of little surprise that Bach was sending mixed messages. Politics? Yes, please. But only when it is controlled to suit our PR mission.

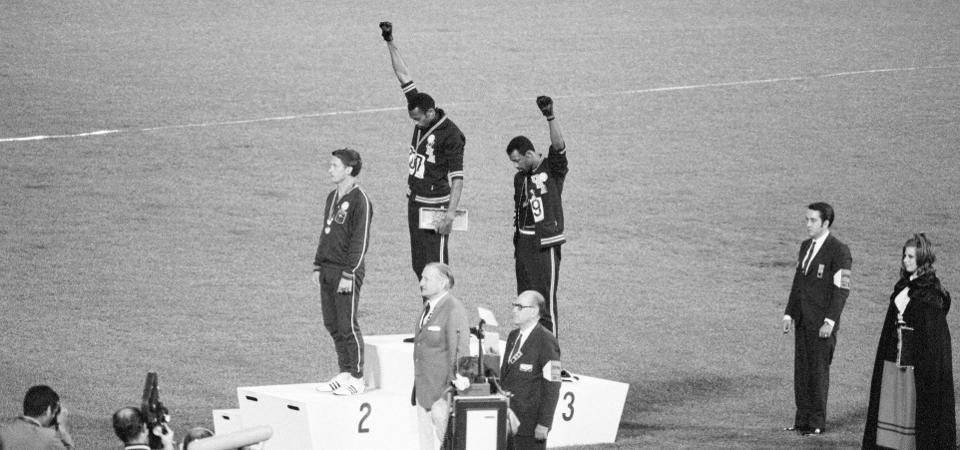

Some of the iconic moments of Olympic history have been full of political symbolism. John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising black-gloved fists on the podium in 1968; Vera Caslavska turning her head away from the Soviet flag in the same year; Jesse Owens winning two gold medals as Adolf Hitler watched on in 1936. As far back as 1906, Peter O’Connor scale a twenty-foot flagpole to draw attention to the struggle for Irish independence.

(Eingeschränkte Rechte für bestimmte redaktionelle Kunden in Deutschland.

ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES

O’Connor’s protest was scowled upon by the authorities, but he was let of with a warning and continued to compete. He went on to win three more medals at the games and each time waved a green flag on the podium. Yet if he were transported 114 years into the future, he would find the authorities a great deal less accommodating.

Read Also: Kashmir Avalanche: Girl Rescued After 18 Hours In Snow

Political protest at the Olympics is already banned under Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, but last week, in the face of rising activism from athletes and a tense global political climate, the IOC, in the form of Bach and IOC Athletes’ Commission Chairwoman Kirsty Coventry, felt the need to expand.

“We needed clarity and they wanted clarity on the rules,” said Coventry. “The majority of athletes feel it is very important that we respect each other as athletes.” According to the three-page document written by the Athletes’ Commission, then, political hand gestures, kneeling, signs and armbands are all big no-nos. And don’t even think about disrupting a medal ceremony.

LIMA, PERU – AUGUST 09: Gold medalist Race Imboden of United States takes a knee during the National

GETTY IMAGES

The hypocrisy of the IOC’s ban on political protest is clear. The Olympics and the bodies that organize them are political by nature. Carlos Nuzman, the head of the Organizing Committee during the 2016 games, was arrested in 2017 suspected of corruption. The regenerative effect that the Olympics were supposed to have in Rio de Janeiro, meanwhile, has gone up in a puff of smoke.

Similarly after the 2012 games, the supposed regeneration of a run-down area of east London — a political project — has had the effect of pushing up property rental prices and forcing people out of the area they used to call home. Beijing 2008? Well, if that was not a ostentatious display of geopolitical power, it is difficult to say what is.

International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Thomas Bach (L) and Chair of the IOC Athletes

So, telling athletes to keep their noses out of politics wreaks of double standards. ‘Leave the serious stuff to the adults,’ Bach may as well have added. Or at least, ‘Leave it to the people who have to secure sponsorship and broadcasting contracts.’

In addition to their hypocrisy, the Athletes’ Commission’s guidelines are utterly self-defeating. Political protest is an act of defiance, an inversion – if often only a temporary one – of power relations. Protests work by drawing attention to a certain issue, by thrusting it into the public consciousness.

Banning such acts only serves to increase their power. It makes any athlete’s defiance more defiant. It means that any act of political protest will go immediately to the top of the news agenda, exactly as the protester would wish.

LONDON, ENGLAND – AUGUST 09: Megan Rapinoe #15 of the United States poses with her gold medal

GETTY IMAGES

Specifying the types of political protest that are not allowed only intensifies that effect. Imagine for a second that you are an American athlete trying to protest against institutionalized racism in the US. Not allowed to kneel? Right, I’ll definitely do that then. No ‘politically motivated hand gestures’? I’ll certainly be sticking my fist up on the podium in that case.

Athletes, the IOC Committee also announced, will face a triple disciplinary procedure if any of these rules are broken, from the IOC, the governing body of the sport itself and the national Olympic committee that the athlete represents. That will inevitably be a long, drawn out process, keeping the story going for far longer than it otherwise would.

The IOC might have reiterated and codified their ban, but whether athletes listen is still very much up to them. And, as US soccer star and 2012 Olympic gold medal winner said on Instagram after hearing the news, “We will not be silenced.” If she is right — and one can only imagine she is — then the IOC’s ban has amplified their voice.

FORBES