Addis Ababa/Nairobi/Brussels — What’s new? African leaders meet in Addis Ababa this week for the annual African Union (AU) summit. This year’s theme is “Silencing the Guns”, reflecting the continental body’s earlier aspirations to end conflicts and prevent genocide in Africa.

Why does it matter? The AU has assumed greater responsibility for conflict management in Africa, with some successes, including recently in Sudan and the Central African Republic. Yet on many conflicts it could do more. African leaders appear increasingly less committed to collective peacemaking and warier of the AU’s peace and security role.

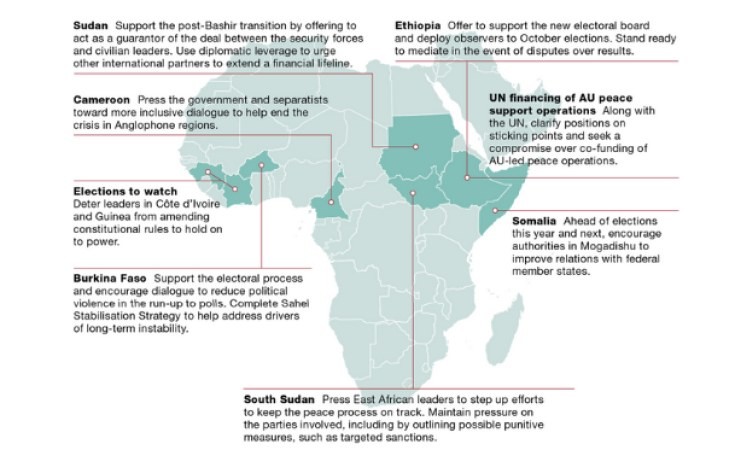

What should be done? The AU itself and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who assumes the rotating AU chair for 2020, should use the Addis meeting to spur African leaders into more rigorous efforts to tackle the continent’s deadliest crises. This briefing sets out eight priorities for the body this coming year.

Overview

African leaders will meet in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, this week for the annual African Union (AU) summit. This year’s theme is “Silencing the Guns”, reviving an aspiration set out by African leaders in 2013 to end war and prevent genocide on the continent by 2020. Though the aim of resolving all conflicts in seven years set the bar high, the AU has scored some successes.

Just this past year, for example, it stepped in at critical moments to preserve Sudan’s revolution and stop it from descending into violence; and helped produce an agreement between the government and rebels in the Central African Republic (CAR). Elsewhere, however – from Cameroon to the Sahel to South Sudan – it has fallen short. Moreover, African leaders today appear cagier than in the past about collective peacemaking, with some apparently wanting to restrain the continental body’s peace and security role. South Africa, which will assume the rotational AU chair when the summit starts, could use the meeting to reinvigorate African efforts to calm the continent’s deadliest crises.

The AU made notable interventions in two major crises in 2019. The Peace and Security Council (PSC), the continent’s standing decision-making body for conflict prevention, management and resolution, showed its mettle after President Omar al-Bashir’s ouster in Sudan. Despite opposition from the AU chair, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the PSC suspended Sudan’s membership in early June after the military putschists massacred peaceful protesters. The AU then helped mediate be- tween civilian and military leaders. The AU also asserted its primacy in CAR’s peace process, sponsoring an agreement between the government and fourteen rebel groups while absorbing a Russo-Sudanese initiative that threatened to become a parallel dialogue. The deal may not have significantly reduced violence, but it renewed outside attention to the crisis and united diplomats behind a single mediation effort.

In other countries, the AU has not been so successful. It failed to prevent the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon from spiralling into almost full-blown civil war; it has largely been a bystander to the instability sweeping the Sahel; and it has taken a back seat in efforts to end South Sudan’s brutal conflict. More broadly, while it has spoken out against coups, it has struggled to respond to rigged elections or to leaders’ schemes to change rules in order to hold on to power. Particularly worrying is that African leaders’ commitment to multilateral efforts to tame conflicts across the continent seems to have waned. The PSC rarely meets at the heads of state level.

Despite the supposed focus on “silencing the guns”, the forthcoming summit’s draft agenda suggests that discussions on peace and security will not take centre stage and that the number of planned high-level side meetings about individual conflicts will be fewer than in past years. If true, that would be cause for regret, as many crises on the continent would benefit from greater and more sustained engagement from African leaders. AU housekeeping in 2020 also risks sapping attention from peacemaking. First, preparations for the 2021 selection of a new commission, the AU’s secretariat, could hamper work. Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki and other commissioners will be eligible for re-selection under new, more rigorous recruitment procedures. They will likely campaign to retain their posts, which is reasonable, but they ought not to let core business slide.

Secondly, a merger of the political affairs and peace and security departments is under way. The amalgamation makes sense, as the two departments’ tasks are inextricably linked: politics lie at the core of most of the continent’s conflicts and efforts to resolve them. But African leaders view the merger as an opportunity to axe jobs, save money and weaken the commission, whose influence in the area of peace and security many regard warily. Current proposals envisage a more than 4o per cent cut in positions. Such a large cull of already understaffed departments would be devastating to morale and reduce the AU’s ability to respond to continental crises. Member states should reverse course and ensure that the commission is adequately staffed and resourced.

The February summit provides an opportunity for the AU and African leaders to make a clear statement of intent toward ending some of the continent’s worst crises. South Africa will take over the rotational chair from Egypt when the summit starts and has made “silencing the guns” a priority for its term at the organisation’s helm. South Africa has punched below its weight abroad for more than a decade, but sim- ultaneously holding the AU chairmanship and a seat on the UN Security Council should provide Pretoria with a rare opportunity to focus attention on conflicts that are important not only to its national interests but also to the AU and UN agendas. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa should seek to spur African leaders into more rigorous efforts to promote peace and security on the continent. Eight areas where he and the AU can focus during the course of the year are:

1. Seeking a compromise with the UN over co-funding of peace operations.

2. Supporting pivotal elections in Ethiopia and standing ready to mediate in the event of disputes over results.

3. Deterring leaders in Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea from using constitutional amendments to hold onto power.

4. Helping calm Burkina Faso’s insurgency and avert election violence.

5. Pressing Yaoundé and separatists toward more inclusive dialogue to help end the crisis in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions.

6. Pushing the Somali government and regional leaders toward a compromise ahead of Somalia’s elections.

7. Pressing East African heads of state to step up their efforts to keep South Sudan’s peace process on track.

8. Supporting Sudan’s transition by offering to act as a guarantor of the deal between the security forces and civilian leaders.

While not exhaustive, this list represents opportunities where the AU likely can have the greatest impact over the coming year. The steps outlined below will not silence the guns across Africa, but they would go some way toward curbing the destruction and trauma wrought by the continent’s worst wars.

I. Seek a Compromise with the UN Over Co-funding of Peace Operations

The AU and the UN have been wrestling for more than ten years with the question of whether UN assessed contributions might be used to support AU peace support operations. But over the last two years the discussions have become more intense – and more fraught. In September, the AU pressed pause on negotiations over a deal that might allow for UN co-financing of certain AU missions so that its leaders could review key elements of the proposed arrangement and formulate a common position. At the core of the discussion is the AU’s effort to secure an agreement whereby the UN would cover 75 per cent of the costs for Security Council-authorised, AU-led peacekeeping missions and the AU would cover the remaining 25 per cent.

An arrangement along these lines would serve both the AU and the UN, neither of which is well positioned to face the continent’s rapidly changing conflict dynamics without the other’s help. While the AU is willing and able to mount the type of counter-terrorism and peace enforcement missions now regularly needed to help stabilise African countries, it lacks the financial resources necessary to provide them steady and predictable support – something the UN can offer. For its part, the UN Security Council stands to benefit from the AU’s willingness to undertake challenging missions that have peace and security ramifications well outside Africa, and that are beyond the scope of traditional UN peacekeeping operations.

Nonetheless, the need to work through complex, politically loaded issues has made it difficult to come to terms on a co-financing arrangement. In recent years, AU-UN talks have foundered on three of these. First, the parties have been unable to reach a clear understanding about how the AU would meet its financial obligations under the proposed 25:75 split in practice, with some Security Council members doubting the African body’s will honour its commitment.

Secondly, Security Council members have questioned the capacity of AU missions to comply with both international human rights law and the UN’s financial transparency and accountability standards. Finally, the two institutions have sparred over which of them should have overall command of the forces.

The timeout in negotiations presents a much-needed opportunity for the AU and UN to clarify their respective positions and to decide how far they are willing to go to achieve a compromise. If the two institutions want to make co-financing work, the outlines of a deal appear within reach: the AU could offer troop contributions (which it would not ask the UN or donors to subsidise) as an in-kind payment toward the 25:75 burden sharing formula; the UN could give greater credit for the progress the AU has made in setting up human rights compliance mechanisms while recognising that the real test of compliance will only come once missions are under way; the AU and UN could rely on the UN Fifth Committee to police financial governance; and the parties could require force commanders to report to both organisations.1

That deal might not be perfect from either side’s perspective, but it would be bet- ter than the alternative, which would require AU peace support missions to continue struggling under ad hoc financial arrangements and risk leaving critical peace and security needs in Africa unmet. The parties have a chance to get an agreement that would help both institutions fulfil their common mandate to prevent, manage and resolve conflict in Africa. They should take it.

II. Prepare to Support Ethiopia’s Election

Ethiopia, the continent’s second most populous country, is in the midst of a promising but turbulent transition. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government pledges that elections tentatively scheduled for 16 August 2020 will be the most peaceful and competitive in the country’s history. But growing intercommunal friction, which has left hundreds dead and displaced millions over the last few years, threatens to mar the vote – or even derail it – because leaders could try to manipulate social divisions to their advantage. The AU is understandably reluctant to intercede in domestic Ethiopian affairs, not least because its headquarters is located in the capital, Addis Ababa. But given the critical importance of the elections for the country’s transition and stability, it should offer to support election preparations and to send a large observation team. It should also be ready to mediate in the event of disputes over the ballot’s outcome, if invited to do so.

Since coming to power in April 2018, riding mass protests that began in 2014, Abiy has made major strides toward opening up the authoritarian system he inherit- ed: freeing political prisoners; allowing the return of dissident groups; and appointing reformers to key institutions, including the refreshed National Electoral Board of Ethiopia. But this very openness has allowed ethnic tensions that were once buried, including longstanding resentments among and within the three most influential communities, the Oromo, the Amhara and the Tigray, to surface. The election could further entrench ethno-regional fault lines, while continuing insecurity might make it difficult to conduct a credible poll.

Ethiopia’s inexperienced new electoral board is under pressure to organise nationwide elections in less than seven months. The institution won praise for its management of the November 2019 referendum on regional statehood for Sidama Zone, but the forthcoming polls present a much greater challenge. The electoral board’s incapacity is already showing: it has yet to undertake voter registration or publish electoral regulations. The AU should offer technical support to the board, including advice on election security and dispute resolution.

The AU should also signal its readiness to send an election monitoring mission. The vote’s sheer size and complexity – there will be around 50,000 polling stations and 250,000 staff – requires a large observer team. It should deploy well in advance of the polls, so as to cover the whole country, and pay particular attention to potential flashpoints. The AU can also play a valuable role in coordinating international monitors, as it did during Kenya’s disputed 2017 election, when it shared information and issued joint statements with the EU and other observers. Selecting a head of mission with the political weight and experience to act as a mediator, if needed, would be a useful precaution. The AU – and the mission, once it deploys – should also call on Ethiopian leaders to dial down the inflammatory rhetoric that increasingly mars the transition.

III. Avert Violence Fuelled by Leaders Changing Rules to Hold on to Power

In addition to Ethiopia, 21 other African countries are due to hold presidential, parliamentary or local elections in 2020.2 Many of these countries are suffering or recovering from conflict, and contentious polls could spark bloodshed. In some cases, “constitutional coups” – ie, attempts by incumbents to change rules in order to extend their tenure in office – risk fuelling anger and increasing the threat of election-related violence. Since its foundation in 2002, the AU has strongly condemned military takeovers, ostracising perpetrators to the point that few are still willing to carry out such overt coups.

Yet it has been less censorious of leaders’ circumvention of term limits. Its inability or unwillingness to speak out undermines its important position against unconstitutional changes of government. In 2020, elections in Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea in particular risk generating violence due to highly controversial consti- tutional revisions against which the AU should take a stronger stand.

In Côte d’Ivoire, President Alassane Ouattara, who has already served two terms, has made conflicting statements about whether he will seek re-election in October. He declared several times that he may not stand again. Recently, however, he has said he will announce his final decision in July 2020. He has also threatened to run if his main rivals – in particular ex-president Henri Konan Bédié – decide to contest the vote. Ouattara fears that Bédié could beat his preferred successor, Amadou Gon Cou- libaly, the current prime minister. The president has also long maintained that a third term is viable, despite the two-term limit in the constitution. He argues that the constitution is new, having been approved in 2016, and that the terms he served before it came into force do not count against the two-term limit.3

Bédié himself is in advanced discussions with another former president, Laurent Gbagbo, over forming an alliance between their respective parties. If such an alliance comes into being, Ouattara’s party will face a significant opposition coalition, which could lead to a very tight contest. In a further complication, Gbagbo himself now threatens to return to Côte d’Ivoire after being acquitted of crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court. His return could spark renewed conflict: his refusal to admit defeat to Ouattara in a 2010 vote set off violence in which more than 3,000 people died. The possible combination of Gbagbo’s return and a simultaneous bid by Ouattara for a third term could raise the spectre of a reprise of the 2010 blood- shed, particularly if Gbagbo’s supporters take to the streets and clash with either security forces or Ouattara loyalists.

The AU, together with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel, UNOWAS, should urge Ouattara to stand down. They should also call on leaders to avoid rhetoric that could inflame tensions and press them to pledge to pursue legal avenues – and no others – in the event of a contested outcome. The two institutions should also offer to send election observers.

In neighbouring Guinea, at least 30 people – mostly protesters – have died since October 2019 during demonstrations against a possible constitutional change that could enable 81-year-old President Alpha Condé to run for a third term. While the current constitution sets a two-term limit, the proposed revision does not explicitly state whether the changes would entail a reset of term limits.

This leaves open the possibility that Condé could contest the October election. Many believe he will. That Condé organised in 2018 the removal of the constitutional court president, who had made clear he would not support an interpretation of the constitution that would permit the president assuming a third term, has done little to dispel concerns. The president’s supporters have been campaigning for a third term for months already.

To avert further violence, the AU, together with ECOWAS, should call on Condé to refrain from amending the constitution in a manner that would allow him another term and encourage him to rule out running again. They should press the government to allow the opposition to campaign freely and ensure that members of the security forces responsible for recent assaults on civilians are held to account. In the meantime, the AU and ECOWAS should signal their willingness to send election observers to Guinea as well.

IV. Help Burkina Faso Contain its Rural Insurgency and Avoid Electoral Violence

The turmoil in Burkina Faso shows no sign of abating in 2020. Fighting between security forces and Islamist militants in the north has intensified and spread east and south since 2016. In addition, banditry, herder-farmer competition and land disputes have fuelled local intercommunal conflicts. So, too, has the proliferation of “self-defence forces” – vigilantes who aid the army against militants. The AU has typically viewed Burkina Faso through the lens of Mali and the Sahel, but rising instability means that the country should receive more specific attention.

The overall death toll from violence in 2019 was greater in Burkina Faso – where more than 2,000 people were killed – than in Mali, usually considered the epicentre of the Sahel’s storms.4 More than half a million people have fled their homes. An estimated 1.2 million need urgent humanitarian assistance.5 While conflict is concentrated in rural areas, tensions in towns and cities, particularly the capital Ouagadougou, are also on the rise. Last year, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project recorded 160 protests against poor living conditions, the lack of economic reform and the government’s failure to stem the insurgency. Some of these protests became full-blown riots.

The unrest could compromise the legitimacy of legislative and presidential elections scheduled for November. Both government and opposition are scrambling to maintain their influence, and may mobilise vigilantes to control turf, push their own voters to the ballot box and deter those of their rivals. The more vigilantes they enlist, the more likely it is that violence will mar the campaign. The authorities are increasingly resorting to repression to quiet mounting criticism, arresting activists and cur- tailing opposition parties’ activities. The focus on the elections also means that the government is directing much-needed attention away from tackling the insurgency. The AU can take steps to deter violence around the polls and protect their integrity.

Together with ECOWAS, the UN and the EU, it should urge the government and opposition to build on a dialogue that took place last July in order to agree on electoral parameters and reduce political violence, particularly communal clashes. It should continue to provide technical assistance to the electoral commission, building its capacity in security and dispute resolution. An AU election observation mission could play a role in discouraging violence during the ballot and will be all the more important because the EU appears unlikely to deploy observers. If invited, the AU should send a monitoring team headed by a political heavyweight who might also be able to assume a mediation role if required.

The AU should also aim to tackle other drivers of instability in Burkina Faso. First, it could press the government to curb armed forces’ abuses and limit their reliance on vigilantes in fighting militants. The AU should quickly complete and begin carrying out its stabilisation strategy for the Sahel. In particular, it should help the Burkinabé authorities formulate a national plan to resolve disputes over land and natural resources that help fuel jihadist expansion and other conflicts. The AU’s Sahel strategy also ought to encompass vigilantes’ demobilisation, or at least better regulation of their role, a reduction in security forces’ abuses, and the return to the countryside of basic services, including health, education, dispute resolution mechanisms and economic development. Though the AU’s Sahel plan will be just one entry in a crowded field of such plans, the continental body has the advantage of being able to work more closely with sub-regional blocs and Sahel governments. Thus, the AU could win greater local buy-in for its proposals.

V. Push for Inclusive Dialogue in Cameroon

Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis has claimed around 3,000 lives since 2017 and taken a severe toll on citizens. Fighting between separatist rebels and security forces in the Anglophone North West and South West has left around 700,000 people internally displaced and forced 52,000 to flee to Nigeria, according to the UN.6 Half of all Anglo- phones now need humanitarian assistance – fifteen times more than three years ago when the conflict began.

For the fourth year in a row, schools are closed in Anglo- phone areas and 800,000 children (85 per cent of the Anglophone school-age population) now have no access to education.7 Without externally mediated talks between the government and separatist leaders, conditions almost certainly will get even worse. The AU needs to move Cameroon up its peace and security agenda and encourage the warring parties to engage more deeply in an inclusive dialogue. It should also push the Cameroon government to allow an AU observer mission for February’s legislative and municipal elections, and press all parties to defuse ethnic tensions across the country ahead of the polls.

A recent government-controlled national dialogue, held at the end of September 2019 has done little to prevent the Anglophone crisis from deepening.8 Separatists, whose leaders are mostly based outside the country or in prison in Yaoundé, were not invited to the consultations, and viewed them as a government ploy to deflect inter- national criticism. Even those Anglophones who seek a federalist solution rather than their own state were given little room to present their views. The officials responsible did not provide the dialogue participants the chance to discuss recommendations that were transmitted to the president. These included the idea of special status for the South West and North West under the decentralisation provisions of the 1996 constitution, but overall offered little new. If anything, the national dialogue strengthened the separatists’ resolve to pursue their rebellion and empowered hardliners on both sides.

The AU has so far taken only limited steps to help resolve the worsening conflict. Among the most recent was a tripartite mission to Cameroon in November 2019 along with the Commonwealth and the International Organisation of la Francophonie aimed at reducing violence and, in the mission’s own words, “increasing national cohesion”. The African Commission of Human and People’s Rights has condemned abuses committed during the crisis. But the AU PSC, the body charged with maintaining continental peace and security, has declined to add the Anglophone crisis to its agenda, largely due to lobbying from Yaoundé. If Cameroon joins the PSC in April 2020, as seems likely, it will be even harder for the council to discuss the conflict.

It is critical for the government to build on its national dialogue and enter mediated talks with Anglophone leaders of all stripes, which would likely mean shuttle diplomacy by a third party. Confidence-building measures on both sides are also required: the government should release a number of detainees and rebels should signal their willingness to accept a ceasefire. The government also should talk directly to all dissenting Anglophones in order to draw them away from the armed struggle. As a first step, it should allow an Anglophone forum, the Anglophone General Conference, to meet. The conference would bring together a wide range of Anglophones and help them forge a united position.

The PSC should urgently consider tabling Cameroon as part of a strategy of public pressure aimed at pushing both sides to compromise and enter negotiations. Optimally, it would ask Faki to appoint a special envoy for Cameroon, who would seek to liaise between the government and rebels. The AU should also renew its offer to mediate and help mobilise other key actors, such as the UN and the Catholic Church, to press both sides to agree to talks. AU leaders and potentially influential current and former African heads of state could be instrumental in moving President Paul Biya to agree to an inclusive dialogue.

Cameroon’s February municipal and legislative elections risk fuelling further violence, both in the Anglophone regions and elsewhere. Most Anglophones appear uninterested in the contests. In any case, many would struggle to vote: hundreds of thousands have been displaced, and there are no provisions for their participation; at the same time, separatists have kidnapped candidates, attacked election offices and vowed to obstruct the polls. The government has assured Anglophones they will be able to cast ballots, deployed additional troops and clustered polling centres to better secure them. But voters will still be unable to travel safely on election day. The main opposition leader, Maurice Kamto, a Francophone, has called for voters not to take part, fearing that holding the ballot without Anglophone participation would only strengthen the separatists’ claim to their own state.9 The AU should also urge the government to engage with Kamto and other political party and civil society leaders to address rising ethnic tensions, especially between the Bulu, President Biya’s community, and the Bamileke, that of Kamto.

VI. Press for Compromise Ahead of Elections in Somalia

Somalia is due to hold parliamentary and presidential elections in December 2020 and early 2021, respectively, but fraught relations between the federal government of President Mohamed Abdullahi “Farmajo” and Somalia’s regions, or federal member states, threaten to blight the ballot. These tensions will likely increase as elections draw closer. Al-Shabaab, Somalia’s Islamist insurgency, may well take the opportunity to step up its violent campaign. AMISOM, the AU’s counter-insurgency mission in Somalia, can play a key role in minimising such violence during election season. More immediately, the AU should step up efforts to reconcile Mogadishu and federal member states ahead of the vote.

Al-Shabaab remained a potent threat across much of East Africa in 2019, con- ducting attacks both inside and outside Somalia. On 28 December, a bomb blast near a crowded checkpoint in the capital killed approximately 100 people, more than 90 of them civilians. The January 2019 raid on the Dusit complex in Nairobi, along with last month’s storming of an air base used by the U.S. military on Kenya’s north coast, illustrate the group’s enduring audacity and agility outside Somalia’s borders. Al- Shabaab’s resilience stems in part from its ability to navigate complex clan politics, provide basic order and services in areas it controls, and raise funds through taxation and extortion.

The militant group’s endurance also stems from the federal government’s tenu- ous grip on security, which is loosened further by competition among elites. With an eye on the forthcoming elections, Farmajo has been trying to instal allies at the head of key federal member states, despite local resistance. In Jubaland, the federal gov- ernment refused to recognise state president Ahmed Madobe’s re-election in August, amid concerns about the conduct of the poll and government claims that the candidate selection process violated the constitution.10 As a result, relations between Jubaland and Mogadishu are essentially frozen. The situation is not much better in Galmudug, where leaders from across the political spectrum have rejected Mogadishu’s interference ahead of scheduled local elections.11

At their core, tensions between Mogadishu and the regions centre on unresolved questions about federal versus state powers and the distribution of resources, over- laid with fundamentally divergent visions of what federalism means in practice. Recently, some member states have complained that the federal government has not consulted them adequately in putting together new legislation, such as a bill to regulate the petroleum sector and another on the electoral system.

Tensions are likely to deepen as elections approach. The polls are due to be held under universal suffrage for the first time since 1969 (past elections have been indi- rect, using an electoral college – involving only about 14,000 voters – based on the clan system). The government maintains its commitment to providing all Somalis the franchise. Voter registration is expected to begin in March, but sizeable parts of the country under Al-Shabaab control will be inaccessible. In addition, federal mem- ber states are unhappy with the new electoral law, in particular one article which could pave the way for an extension of Farmajo’s term in office if elections cannot be held as scheduled. A May 2019 meeting between the government and federal state leaders aimed at resolving this dispute, among others, collapsed without resolution.

The AU should press Mogadishu to improve relations with federal member states. A starting point could be fresh talks between Farmajo and the regional presidents in a format similar to the National Leadership Forum, which met regularly ahead of the 2016-2017 elections. Such a dialogue would seek to forge agreement on voting procedures. The federal member states might agree to work with the federal government to ensure that elections run smoothly, and in return Mogadishu could agree to greater consultation with the regions on electoral rules. It may be necessary to delay passage of the electoral law in the upper house even if that affects the electoral calendar. The AU could seek to broker such a compromise. AMISOM, which can reach dangerous areas of the country that are off limits to the UN and other partners, will be vital to maintaining security during the ballot, especially if the government does attempt to extend the franchise to Somalis across the country.

VII. Keep South Sudan’s Beleaguered Peace Agreement on Track

South Sudan’s peace process is floundering. A ceasefire in place since the latest peace deal, signed in September 2018 by the two main belligerents, President Salva Kiir and his former vice president Riek Machar, is thankfully holding. The truce enables South Sudanese to return to their villages to cultivate crops and avail themselves of basic services and humanitarian aid. But it could break down if Kiir and Machar do not settle their disputes. Less than a month remains before a 22 February deadline by which Kiir and Machar are to form a unity government. Sustained high-level mediation is urgently needed if they are to stand any chance of hammering out agree- ments on their differences before then. The limited engagement by East African heads of state over the past eighteen months gives little cause for optimism that they will play this role. As an architect of the original 2015 peace agreement, which failed in part due to insufficient outside involvement, the AU should redouble its efforts to ensure that the current accord remains on track.

Three key issues that were set aside in the September 2018 deal still need to be resolved.

The first and immediate hurdle is the fraught question of the number and demarcation of states within South Sudan, which effectively establishes the distribu- tion of power across the country. In 2014, Machar called for a 21-state division, but Kiir subsequently redrew the map, creating 28 and then 32 states, so as to favour his political base. South Africa’s deputy president, David Mabuza, proposed a 90-day arbitration period that would extend past 22 February. Machar rejected the proposal and demands that an agreement on the configuration of states be reached before he joins a unity government. Anything less would be seen as capitulation by many rebels, risking the fragmentation of Machar’s coalition. A compromise should be possible. Both Kiir’s and Machar’s parties appear to have space to budge from their particular positions without losing critical levels of support. Mediators could also signal that the intransigent party would shoulder the blame for a collapse over the issue.

A second sticking point is army reform: the proposed unification of the 83,000 fighters loyal to Kiir or Machar has lagged due to shortages of food, water and medical supplies, which have forced soldiers to abandon cantonment sites. An important first step would be for Kiir to make sure that the funds he pledged for army unification are actually allocated to related activities and that his troops arrive at designated training sites to allow the new joint units to form. With this gesture he could demonstrate his commitment to rebel forces’ integration. Machar will likely need to give ground on the timeline and the screening of his forces, as well as accept a reduction in the number of troops he can bring into the army.

The third outstanding issue involves provisions for Machar’s personal safety in the capital Juba once the unity government is formed. His return to Juba in 2016 led to the 2015 peace deal’s collapse and fresh hostilities breaking out in the city be- tween his bodyguards and Kiir’s. To prevent Machar from returning to the capital with a large contingent of fighters, the UN Mission in South Sudan or the AU could offer him third-party protection.

Any accord between Kiir and Machar will require concerted diplomacy by regional leaders. Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni and General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, chairman of Sudan’s Sovereignty Council, brokered the deadline extension in November, the first such high-level mediation in 2019. But since then, Museveni and Burhan have remained disengaged and mediation by the secretariat of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the sub-regional bloc charged with leading negotiations, as well as heavy engagement on the issue of the number of states from Mabuza and envoys from South Sudan’s neighbours, has proven insufficient to bridge the gaps between Kiir and Machar. For their part, IGAD heads of state have been largely absent due, in part, to disagreements over who should chair the body. Now that Sudan has assumed that role, they should step up. Ideally, IGAD would convene a summit aimed at pressing the South Sudanese parties to find common ground. February’s AU summit provides the perfect venue for spurring IGAD into taking such action.

The AU and other African countries could usefully get more involved. IGAD frequently kicks into gear only when competing mediation initiatives begin to take form. Increased AU interest could lead either to greater IGAD engagement or to talks about how to share responsibility for the peace process or even transfer it away from the sub-regional bloc. AU Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki could appoint an envoy to work with other guarantors, including the UN, EU, the Troika (U.S., UK and Nor- way) and China, to salvage the transition. This approach would borrow from a model used with some success in Sudan. The C5 group of African states (comprised of Algeria, Chad, Nigeria and Rwanda, with South Africa as chair) mandated by the AU to support IGAD’s work on the peace process should also throw its weight behind calls for IGAD members to convene a summit and Kiir and Machar to resolve outstanding issues. The PSC could help by spelling out to Kiir and Machar the punitive measures they will face, including targeted sanctions and diplomatic isolation on the continent, if they fail to reach an agreement by 22 February.

Lastly, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa himself could assume a larger role, as chair of both the AU and the C5. He might, for example, lobby Museveni to convince his ally Kiir that agreeing to compromise on the three outstanding issues is greatly preferable to more years of international isolation. As a sitting head of state, the South African president would also have the clout to mediate directly between Kiir and Machar, an opportunity not yet afforded to Mabuza, Ramaphosa’s deputy and envoy.

Read Also: Africa’s Rising Level Of Malnutrition Is Worrisome – AFDB

VIII. Stay the Course on Sudan

Sudan’s transition remains promising albeit on shaky ground. The country faces acute economic and security challenges, and the population is hungry for change, having seen few dividends since the new administration took office. Keeping the transition on track requires external economic and political support and, in particular, a credi- ble guarantor to maintain the delicate power-sharing arrangement. The AU, which has been instrumental to the transition, is well placed to play that role.

Last year, the AU took strong action at a number of critical moments that helped the revolution survive. First, it condemned the April 2019 military takeover that forced President Omar al-Bashir from office – and by extension refused to recognise the subsequent military government – despite determined support for the putschists among influential member states such as Egypt. Secondly, it suspended Sudan fol- lowing the military’s brutal crackdown on protesters on 3 June. Then, together with Ethiopia, the continental body helped bridge the divide between the civilian coalition and the security establishment, brokering a power-sharing deal that, if it holds, will usher in full civilian rule in 2022.

The transitional administration, led by the widely respected economist Abdalla Hamdok and comprising a largely civilian cabinet, faces formidable challenges. Expectations are high, both inside and outside the country, that it will bring peace to Sudan’s war-ravaged peripheries and overhaul the country’s constitution in preparation for elections planned for 2022, all the while maintaining the fine political balance between its military and civilian members. Its top priority, however, must be to reform and revive Sudan’s ailing economy. Sudanese continue to suffer from ram- pant inflation and inadequate state welfare support. Indeed, if anything, the economic crisis that brought people into the streets in 2019 has intensified. Reversing Bashir’s legacy will almost certainly take time, but the population displays little patience and expects rapid change.

While the AU and its member states are in no position to offer Sudan an economic lifeline, they can use their diplomatic leverage to urge other international partners to do so. As part of the Friends of Sudan forum, the AU should encourage international donors to coordinate their economic support and identify and deliver projects that have near-term benefits for the Sudanese. It could also push for the establishment of a multi-donor trust fund, to be managed by the World Bank, which would support economic diversification away from extractives and reinvigorate Sudan’s agriculture sector.

The AU and its heads of state should also work with European and Gulf countries to press the U.S. to lift its outdated designation of Sudan as a state sponsor of terror- ism. Rescinding the terrorism listing will not solve all Sudan’s problems, but it would encourage international investors to re-engage with Sudan and remove a major obstacle to debt relief worth $60 billion. It would also provide a welcome political boost for the transitional government, particularly its civilian members. To assuage U.S. concerns that the Sudanese security establishment could use the lifting of the terror- ism designation to deepen its control over a more open Sudanese economy, gain influence and even leverage the return of an exclusively military-run government, the AU PSC could consider setting out its own sanctions regime that would target those who impede the political or economic transition.

The absence of an official guarantor jeopardises Sudan’s power-sharing deal. The AU could step up as an informal guarantor by appointing a new special envoy. Operating out of the AU’s liaison office in Khartoum, which would need to be strengthened accordingly, the envoy would support the implementation of the transitional agreement and reform agenda. This task could entail mediating to resolve disagreements between the parties in the transitional administration, who still distrust each other.

In addition, the envoy could oversee any peace agreement struck as the result of talks in Juba between the government and armed groups in the country’s periphery – in Blue Nile, Kordofan and Darfur regions. In any event, the PSC should closely monitor the agreement’s progress, ideally by holding monthly meetings on Sudan.

1 For further details see Crisis Group Africa Report N°286, The Price of Peace: Securing UN Financ- ing for AU Peace Operations, 31 January 2020

2 The following countries will hold elections in 2020: Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Senegal, Somalia, Somaliland, Seychelles, Tanzania and Togo.

3 “Ivorian president says he will stand in 2020 election if former leaders run again”, Reuters, 30 November 2019. “The rise and fall of another African donor darling”, Foreign Policy, 22 January 2020.

4 In 2019, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, there were 2,194 deaths related to armed violence in Burkina Faso and 1,879 in Mali.

5 “Humanitarian Snapshot”, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 9 December 2019.

6 “Cameroon: North-West and South-West Situation Report Nos. 13 and 14”, UNOCHA, 31 Decem- ber 2019.

7 “More than 855,000 children remain out of school in North-West and South-West Cameroon”,

UN Children’s Fund, 5 November 2019.

8 Crisis Group Statement, “Cameroon’s Anglophone Dialogue: A Work in Progress”, 26 September 2019.

9 “Cameroon opposition leader Kamto calls for elections boycott”, France 24, 25 November 2019.

10 “Interior ministry set new procedures to form Jubbaland Assembly”, Halbeeg, 7 October 2019. 11 “Four candidates withdraw from Galmudug presidential poll, accuse FGS of ‘hijacking the pro- cess'”, Goobjoog News, 22 January 2020; “Ahlu Sunnah: Federal Government has hijacked Gal- mudug electoral process”, Goobjoog News, 26 January 2020.

ALL AFRICA