The Nigerian government recently announced that it had released about 1,400 Boko Haram suspects. The reason given was they had repented and were to be re-integrated into society. The government said the releases – which happened in three tranches – were part of its four-year old de-radicalisation programme called Operation Safe Corridor.

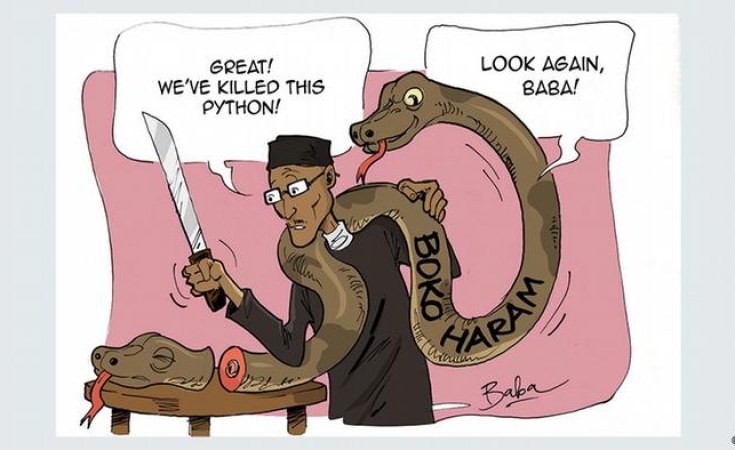

The announcement generated a lot of angst. Opposition leaders attacked the decision, as did soldiers fighting the terrorists.

These reactions mask a fundamental challenge facing governments in conflict situations: how does it deal with defectors? Simply executing combatants, or detaining them indefinitely, aren’t viable options. De-radicalisation and re-integration programmes therefore become unavoidable.

As several commentators on the Boko Haram conflict have repeatedly maintained, such as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a purely military solution won’t defeat the group.

Generally ‘de-radicalisation’ is understood to involve having people with extreme and violent religious or political ideologies adopt more moderate and non-violent views. The approach is predicated on the assumption that terrorists, and others with extremist views, can be engaged in a way that can reduce their risk of re-offending.

But there are a number of questions that ‘de-radicalisation’ and ‘re-integration’ programmes raise. These include: is it possible to screen the combatants well enough to measure what level of threat they pose? This is a problem in a country like Nigeria where the basis of selecting those who are being released isn’t transparent. For example, there are allegations that criminal elements in the military have colluded with Boko Haram to secure the release of unrepentant terrorists.

Another question that’s raised is: how can we ensure that the ‘former terrorists’, if re-integrated into the society, do not end up radicalising others in the community, or becoming spies to their former terrorist masters?

Read Also: Boko Haram Repentant Members Not Recruited – Army

And is it fair to rehabilitate the combatants without also rehabilitating their victims?

Most countries faced with violent extremism and terrorism have adopted one form or another of de-radicalisation programmes. Whether they have worked or not is hard to judge because assessments are very often made by people responsible for the programmes. But one thing is clear: governments don’t have many viable alternatives.

Nigeria’s programmes

Nigeria has three main de-radicalisation programmes. One is located in Kuje prison, Abuja, and was set up by the Nigerian government in 2014. Participants are combatants convicted of violent extremist offences and inmates awaiting trial. The aim of the programme is to combat religious ideology and offer vocational training as a prelude to re-integrating them into communities.

There is also the Yellow Ribbon Initiative which is located in communities in Borno State, in the epicentre of the Boko Haram insurgency in the north of the country. This is organised by a not for profit organisation, the Neem Foundation. It was set up in 2017 and targets women, children and young people associated with Boko Haram.

The third is Operation Safe Corridor, which was set up in 2016 by the government. It targets Boko Haram combatants who have surrendered. This approach targets three key issues: religious ideology, structural or political grievances and post-conflict trauma.

The project engages Imams to work with those in the programme on religion. Participants are also offered training in rudimentary vocational skills. And they are offered therapy to overcome the trauma they faced as members of Boko Haram.

Experiences elsewhere

A wide range of countries have introduced de-radicalisation programmes.

In Africa, the four Lake Chad basin countries – Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon and Chad – have their own versions. In Somalia, the Serendi Rehabilitation Centre in Mogadishu offers support to ‘low-risk’ former members of Al-Shabaab.

In Northern Ireland, the Early Release Scheme ensured the conditional release of convicted terrorists under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. It was deemed essential to sustaining the country’s peace process.

In Colombia, former guerrillas who fought for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia were invited to join a peace building programme called the ‘collective reincorporation’.

Do they work?

There is no consensus on what constitutes success in reforming a terrorist.

There is, however, general acceptance that a narrow focus on recidivism as the key metric has been discredited. This is because the reasons for peoples’ behaviour isn’t always understood. For example, re-offending could well have been stimulated by new impulses after release. On the other hand, not re-offending does not necessarily mean the person has abandoned extremist views.

There is also confusion about whether any kind of rehabilitation is necessarily brought about by the de-radicalisation programme. For example, it could be more about the desire for freedom, or to access some benefits that go with a rehabilitation programme.

Measuring success isn’t easy. Official information is likely to be biased as the state and groups running programmes are wont to paint a rosy picture to justify the expenditure.

Additionally, whether a de-radicalisation programme is deemed successful or not may be subjective depending on what metrics are used. A good example is the research done for the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. It praised Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor to the high heavens, arguing that it was a model of rehabilitation for Africa as well as the Western world. Yet a report for the Carnegie Foundation was very critical of the programme on several grounds. This included a lack of clarity on eligibility and as well as how former combatants would be re-integrated into civilian life.

Not many options

The question often not asked about de-radicalisation programmes is: what’s the alternative?

Framed this way, it’s obvious that governments facing challenges of terrorism and violent extremism have virtually no other alternative.

But that shouldn’t stop criticism of the way in which programmes are run. The Nigerian government’s release of 1,400 former Boko Haram fighters is a case in point. It was handled badly, not least because the public was told after the event.

The timing was also inauspicious. There is currently a resurgence of attacks by the terrorist group. At the same time President Muhammadu Buhari’s government is facing a declining sense of legitimacy . These factors helped harden attitudes and drove the push-back from Nigerians.

ALL AFRICA