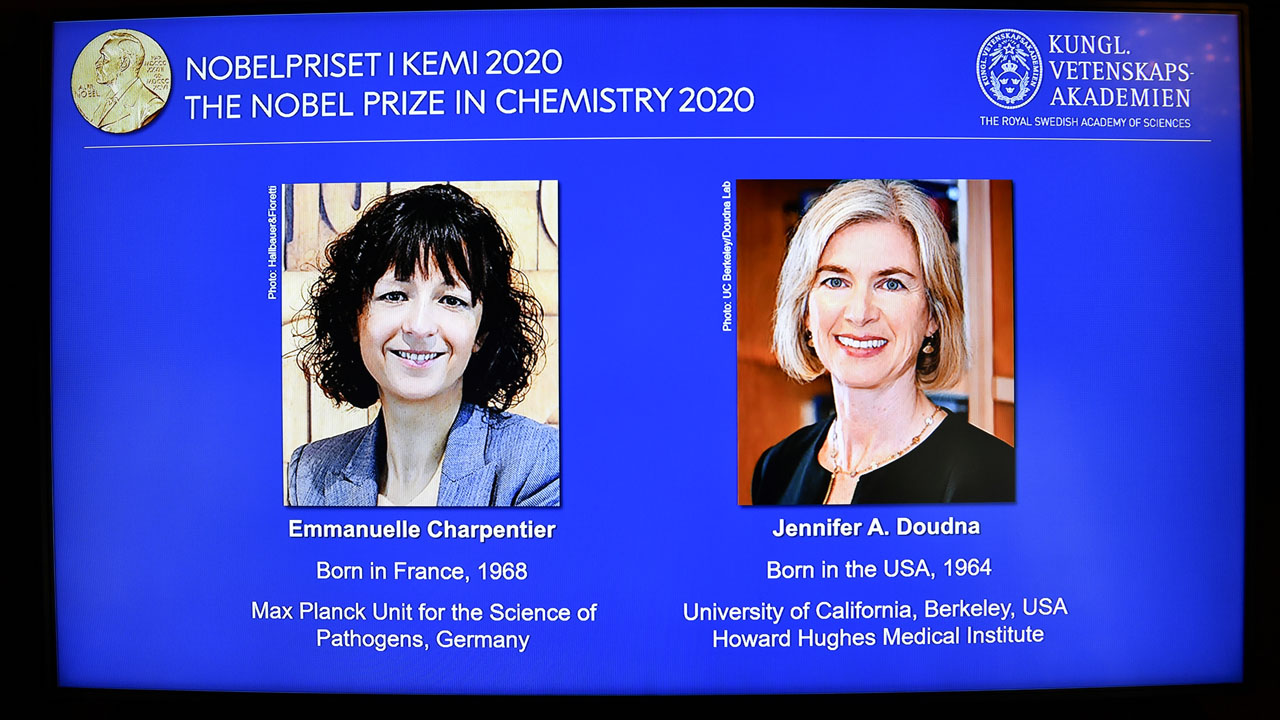

Emmanuelle Charpentier of France and Jennifer Doudna of the US on Wednesday won the Nobel Chemistry Prize for the gene-editing technique known as the CRISPR-Cas9 DNA snipping “scissors”, the first time a Nobel science prize has gone to a women-only team.

Using the tool, “researchers can change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with extremely high precision,” the Nobel jury said.

“This technology has had a revolutionary impact on the life sciences, is contributing to new cancer therapies and may make the dream of curing inherited diseases come true.”

The technique has been tipped for a Nobel nod several times in the past, but speaking to reporters in Stockholm via telephone link Charpentier said the call was still a surprise.

“Strangely enough I was told a number of times (it might happen) but when it happens you are very surprised and you feel that it’s not real,” she said.

Charpentier, 51, and Doudna, 56, are just the sixth and seventh women to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Speaking at a Berlin press conference later in the day, Charpentier said the fact that women were being honoured reflected a changing field with more female scientists.

“Science, fundamental science, becomes slowly, but hopefully surely, a world of female scientists as leaders, and it reflects what is happening in our days,” she said.

Rewriting ‘the code of life’

While researching a common harmful bacteria, Charpentier discovered a previously unknown molecule — part of the bacteria’s ancient immune system that disarms viruses by snipping off parts of their DNA.

After publishing her research in 2011, Charpentier worked with Doudna to recreate the bacteria’s genetic scissors, simplifying the tool so it was easier to use and apply to other genetic material.

They then reprogrammed the scissors to cut any DNA molecule at a predetermined site — paving the way for scientists to rewrite the code of life where the DNA is snipped.

The CRISPR/Cas9 tool has already contributed to significant gains in crop resilience, altering their genetic code to better withstand drought and pests, and led to innovative cancer treatments.

“There is enormous power in this genetic tool, which affects us all. It has not only revolutionised basic science, but also resulted in innovative crops and will lead to ground-breaking new medical treatments,” Claes Gustafsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, said in a statement.

Charpentier currently works as the director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, Germany, while Doudna is a professor of biochemistry at the University of California.

“Only imagination sets the limit for what this chemical tool, that’s too small to be visible to our eyes, can be used for in the future,” Pernilla Wittung Stafshede of the Nobel Committee told reporters.

The professor of chemical biology also noted that it had been widely adopted even though it had only been around for eight years.

Rogue practice

It is not uncommon for scientists to have to wait for decades for their work to be recognised for a Nobel Prize.

“I think the implications of this new technique of CRISPR are so obvious that they are going to really have an impact in the long-range that you don’t really need to wait,” Luis Echegoyen, president of the American Chemical Society, told AFP.

Another question has been whether the CRISPR technique perhaps was a better fit for the medicine prize.

Echegoyen said that the discoveries could have been deserving in both categories, but added that the technique was “really very chemistry centric.”

“At the end of the day, all of these things distill down to hydrogen bonding and pi stacking interactions, so it’s all chemistry, and that’s what made this whole thing possible,” he said.

CRISPR’s relative simplicity and widespread applicability has however triggered the imaginations of rogue practitioners.

In 2018 in China, scientist He Jiankui caused an international scandal — and his excommunication from the scientific community — when he used CRISPR to create what he called the first gene-edited humans.

The biophysicist said he had altered the DNA of human embryos that became twin girls Lulu and Nana.

His goal was to create a mutation that would prevent the girls from contracting HIV, even though there was no specific reason to put them through the process.

“Ethics, laws and regulations are extremely important here as well,” Wittung Stafshede said.

The first time a woman was honoured with the chemistry prize was in 1911 when Marie Curie, who also took the physics prize in 1903, won after discovering the elements radium and polonium.

Her daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie won in 1935 and later winners included Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1964), Ada Yonath (2009) and Frances Arnold (2018).

Charpentier and Doudna will share the prize sum of 10 million Swedish kronor (about $1.1 million, 950,000 euros).

They would normally receive their Nobel from King Carl XVI Gustaf at a formal ceremony in Stockholm on December 10, but the pandemic means it has been replaced by a televised ceremony showing the laureates receiving their awards in their home countries.

AFP