The government of Japan could begin releasing treated but still, radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station into the Pacific Ocean as early as August after the United Nations nuclear watchdog gave the controversial plan the green light following a two-year review.

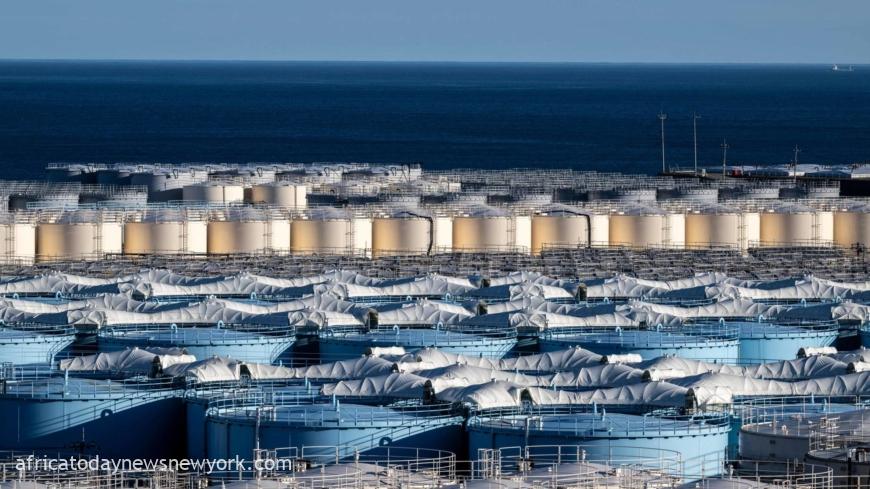

Going by the greenlight, Japanese officials would be expected to explain the plan soon to the local community and neighbouring countries amid concerns about the impact of the release of the water, which is currently stored in more than 1,000 giant tanks around the site of the power station.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Grossi said on Tuesday that the agency’s two-year safety review had concluded the plan was ‘consistent with relevant international safety standards… [and] the controlled, gradual discharges of the treated water to the sea would have a negligible radiological impact on people and the environment’.

Read Also: US Mounts Pressure On Russia, Releases Nuclear Warhead Data

Grossi is expected to travel to the Fukushima site on Wednesday with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

No fewer than 1.3 million tonnes of water – enough to fill 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools – has built up at the plant since the March 2011 tsunami destroyed the power station’s electricity and cooling systems and triggered the world’s worst nuclear disaster since Chornobyl.

Most of the water comes from cooling the three damaged reactors and an extensive pumping and filtration system known as the advanced liquid processing system (ALPS) extracts tonnes of newly contaminated water every day, filtering out most of the radioactive elements.

Still, the plan to release the water, first announced in April 2021, has encountered fierce resistance from Japan’s neighbours and Pacific island nations as well as fishing and agricultural communities in and around Fukushima, which fear for their livelihoods.

Much of the concern has centred on the presence of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, which is hard to remove from water.

The IAEA said that before the discharge, Japan would dilute the water to bring the level of tritium to below regulatory standards and that the UN watchdog would maintain a “continuous on-site presence and provide live online monitoring on its website from the discharge facility” once the release begins.

The process is expected to take several decades.