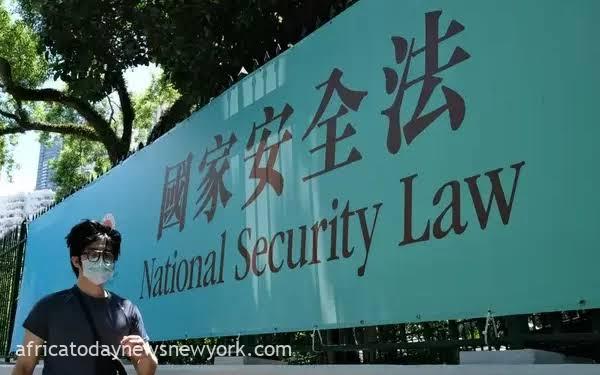

Hong Kong‘s adoption of a stringent security law, deemed essential by authorities to ensure stability, is met with apprehension from critics wary of its potential encroachment on civil liberties.

The fast-tracked passage of Article 23, which encompasses new crimes like external interference and insurrection with life imprisonment as a potential penalty, was facilitated by Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing parliament in less than a fortnight.

Building upon a contentious national security law (NSL) previously imposed by China, Article 23 extends its scope by encompassing offenses such as secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces in Hong Kong.

Despite criticisms, Hong Kong’s leader, John Lee, maintains that Article 23 is crucial in preventing “potential sabotage and underlying currents aiming to disrupt peace,” specifically mentioning “the concept of an independent Hong Kong.” He lauded its implementation as “a historic achievement eagerly awaited by the people of Hong Kong for more than 26 years.”

China’s Vice-Premier Ding Xuexiang earlier said swift enactment of the new legislation would protect “core national interests” and allow Hong Kong to focus on economic development.

Scores of people have been arrested under the NSL since it was passed in 2020, which critics say has created a climate of fear. Amnesty International’s China director Sarah Brooks said the new law “delivered another crushing blow to human rights in the city”, while Maya Wang, acting China director at Human Rights Watch, said it would “usher Hong Kong into a new era of authoritarianism”.

Read also: Hong Kong Mulls Tough New National Security Punishments

“Now even possessing a book critical of the Chinese government can violate national security and mean years in prison in Hong Kong,” she said, calling on the government to repeal it immediately.

Hongkongers have also voiced concerns over Article 23, particularly over the use of broad and vague definitions in the legislation.

Civil servant George told the BBC he was most concerned about its definition of “state secrets”.

“Let’s say a group of colleagues go out to lunch and discuss how to handle some work matters. Will it constitute leaking a state secret? Will we be arrested if someone eavesdrops and spreads the information?” he said.

“I am very afraid that we can be accused [of the offence] easily.”

George observed a pervasive “informant culture” among his peers since the enactment of the earlier law. He calculates that approximately one-fifth of the employees in his department have resigned in the past three years, with a significant number opting to relocate internationally.

“I won’t talk so much about work with friends any more. Just focus on eating, drinking and having fun,” George said.

Similar to others, corporate consultant Liz voices concerns about the recent “external interference” clause, which includes actions such as accepting financial support or directives from foreign governments, political organizations, or individuals, among other external influences.

“The definition of ‘international organisations’ is very broad. Aren’t foreign investment banks and businesses international organisations?”

Following her move to Singapore, Liz is troubled by the prospect of facing prosecution whenever her company releases research reports with her name attached.