AFRICA FINANCIAL REVIEW

The Weekly Journal of Africa’s Capital, Markets & Economy

First Edition | September 1, 2025.

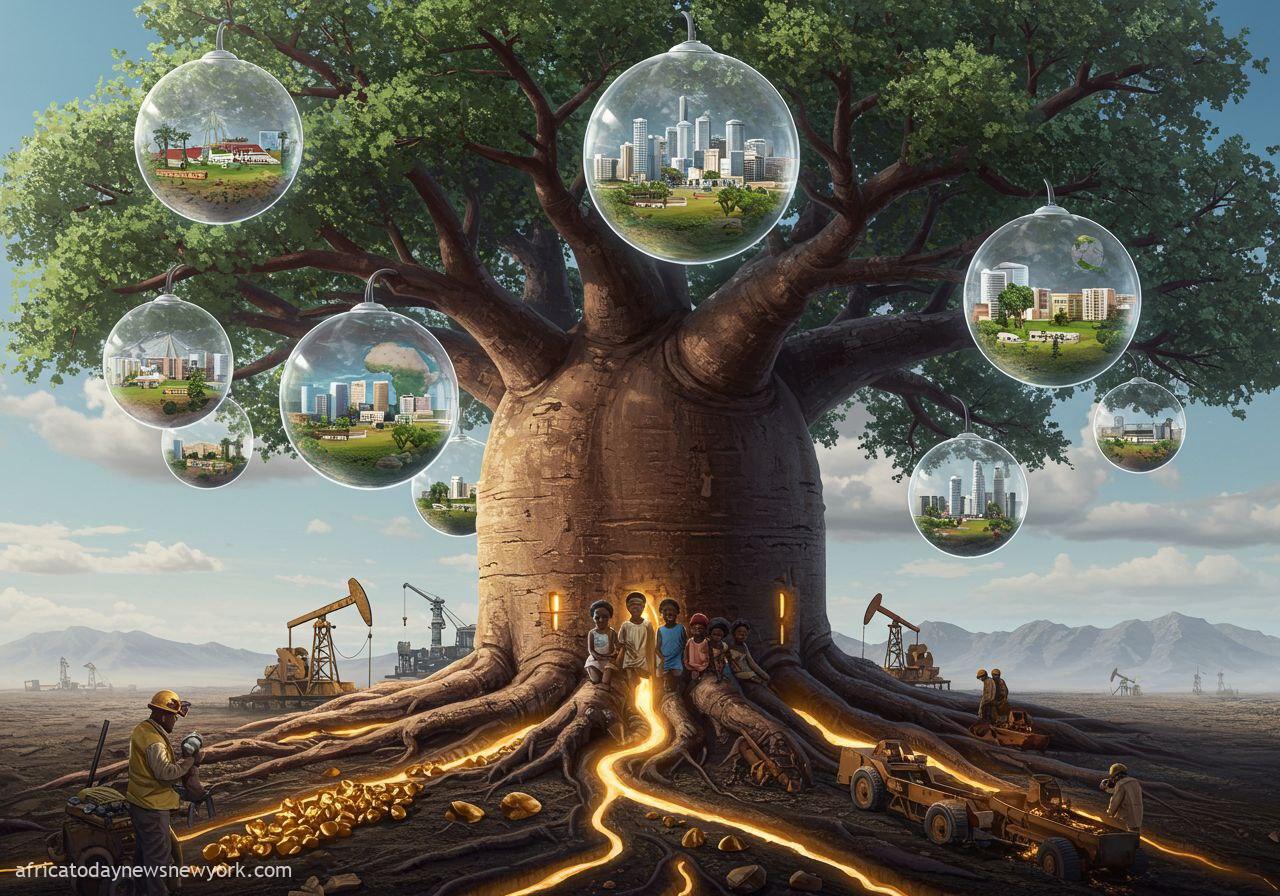

How remittances, sovereign wealth, and global investors are reshaping Africa’s financial destiny.

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert

Editorial Statement

Africa’s financial awakening is not a forecast; it is a reality unfolding in plain sight. For too long, the continent’s economic narrative has been confined to a vocabulary of aid, debt, and external dependence. That framing is now obsolete. Beneath it lies a more complex and compelling story: the billions generated by Africa’s own people, resources, and markets, and the urgent question of whether those billions can be harnessed for sovereignty.

This dossier, Africa’s Hidden Billions: The New Capital Flows, departs from the conventional. It does not treat Africa as a passive stage for external actors but as an emerging financial ecosystem with agency, leverage, and choice. We examine the lifeblood of remittances, the cautious rise of sovereign wealth funds, the surge of foreign investment, and the shadow of illicit financial flows that siphon wealth away. At its core, the series asks a simple but profound question: how can Africa move from being capital-receiving to capital-controlling?

The stakes could not be higher. Africa is home to the world’s fastest-growing population, a consumer market set to rival Asia’s, and resources central to the global energy transition. Yet without financial sovereignty, these advantages risk repeating familiar patterns of extraction and dependency. The continent’s billions will continue to enrich others, not itself.

Our editorial position is clear: Africa must not only attract finance but also retain and direct it toward its own priorities. That requires innovation — diaspora bonds that transform emotional ties into structured capital, regional markets that offer scale and liquidity, and governance systems that build trust at home and abroad. It also requires courage: confronting illicit flows, demanding transparency, and asserting Africa’s right to define its financial destiny.

The dossier that follows is both diagnostic and prescriptive. It illuminates the hidden flows already reshaping Africa and sets out pathways to transform them into instruments of sovereignty. It speaks to policymakers, investors, and citizens alike — those within Africa and its vast diaspora whose choices will define whether the continent’s billions remain hidden, squandered, or harnessed.

Africa does not suffer from a scarcity of capital. It suffers from a scarcity of control. Restoring that control is the defining financial project of the 21st century.

— The Editorial Board

People & Polity Inc., New York

Overview

Africa’s financial story is being redefined. Once positioned as the passive recipient of aid and concessional loans, the continent is increasingly recognized as a dynamic generator and attractor of capital. Beneath the headlines of poverty and aid dependency lie billions in undercounted and underleveraged flows that shape Africa’s present and could transform its future. These are Africa’s “hidden billions”: diaspora remittances, sovereign wealth funds, private capital pools, and illicit outflows that together represent both opportunity and risk.

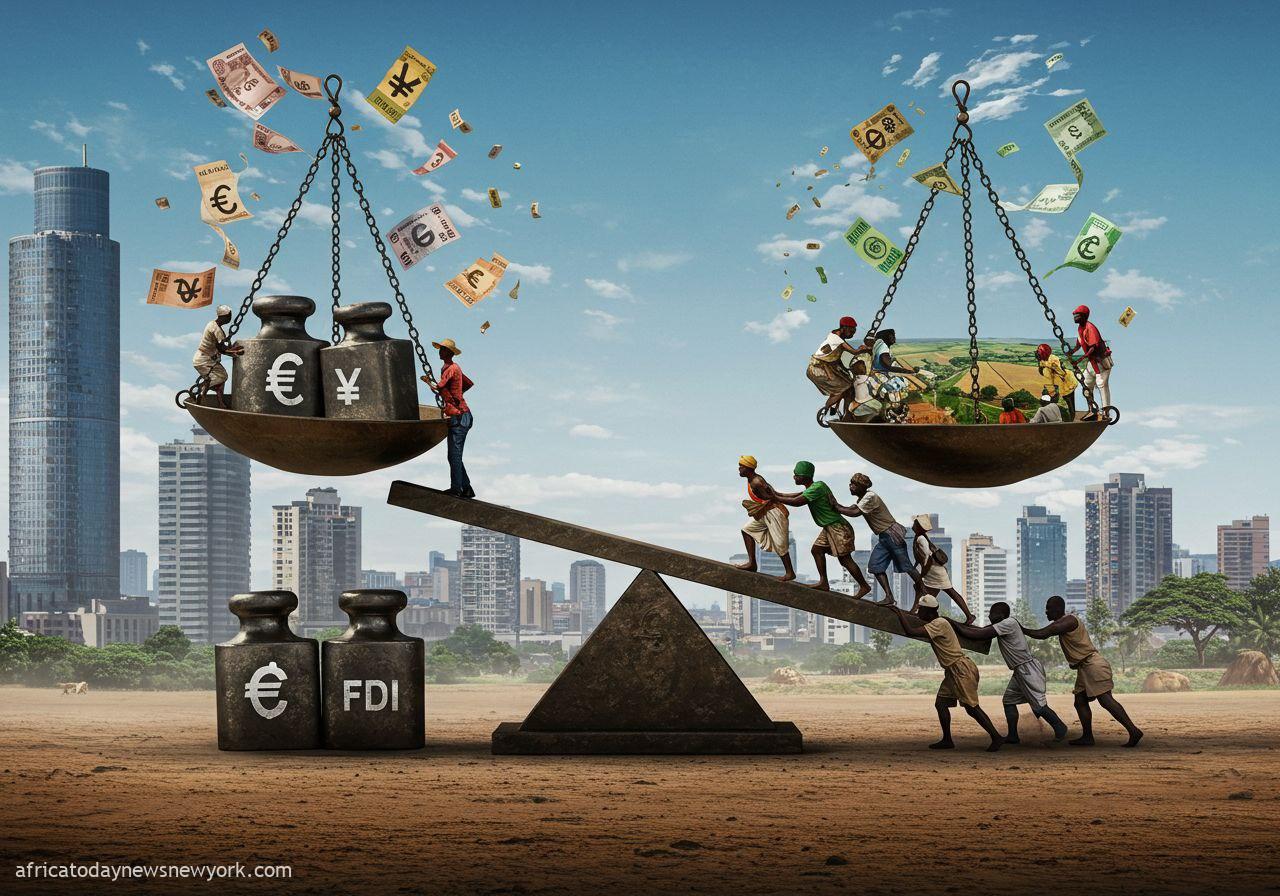

The scale of these flows is striking. In 2024, the continent received a record USD 97 billion in foreign direct investment (UNCTAD, 2025). Diaspora remittances are set to surpass USD 100 billion annually by 2025 (GFRID, 2025), already outpacing both aid and FDI as the most reliable source of external finance. Sovereign wealth funds, though still small by global standards, are expanding across resource-rich states, aiming to convert finite revenues into intergenerational capital. At the same time, Africa hemorrhages an estimated USD 88.6 billion annually through illicit financial flows (UNCTAD & AEF, 2023), undermining the very foundations of development.

This dossier traces six dimensions of Africa’s capital awakening. It begins with remittances — the silent giant that sustains households yet remains underleveraged for structural transformation. It examines sovereign wealth funds as instruments of long-term stability, explores the surge of global investors competing for African opportunities, and interrogates the risks of volatility, debt, and capital flight. Finally, it outlines a path toward financial sovereignty: mobilizing diaspora bonds, building regional financial markets, and aligning flows with Africa’s own priorities.

The narrative is clear. Africa does not lack capital. It lacks control. The continent’s challenge is not only to attract flows but to retain them, harness them, and direct them strategically. Achieving financial sovereignty requires more than technical reforms; it demands trust, transparency, and a bold reimagining of Africa’s place in global finance.

In this sense, the dossier is less about documenting flows than about reframing Africa’s agency. The question is not whether Africa will receive billions, but whether it will convert those billions into sovereignty. For the first time in generations, the continent has both the resources and the momentum to do so. The outcome will define Africa’s 21st century.

Part 1: Africa’s Wealth Awakening

Behind the old narrative of debt lies a new reality: remittances, wealth funds, and private capital reshaping Africa’s future.

1.1 Introduction – Breaking the Old Narrative

For much of modern history, Africa’s financial story has been cast in terms of dependence. The continent was portrayed as a passive recipient of aid, foreign loans, and external interventions. This framing ignored Africa’s own vast and diverse capital flows — resources generated internally or by its global diaspora that quietly sustained households, communities, and national economies.

That narrative is now collapsing. Across the continent, a new reality is emerging. Africa’s “hidden billions” — remittances, sovereign wealth funds, private domestic capital, and illicit financial flows — are increasingly central to the financial future of the continent. These flows, once underestimated or obscured, are now being recognized as transformative. Africa is not merely a passive beneficiary of global capital markets but an active player with agency, leverage, and untapped power.

1.2 The Hidden Billions – Mapping Africa’s Capital Landscape

Africa’s financial ecosystem is far larger and more dynamic than traditionally captured by international statistics. When broadened beyond aid and foreign direct investment (FDI), the picture changes dramatically.

- Remittances – The most visible and reliable of Africa’s hidden flows. According to the World Bank (2024) and the Global Forum on Remittances and Development (2025), diaspora remittances to Africa are expected to exceed USD 100 billion annually in 2024. These flows are already larger than both aid and FDI combined.

- Sovereign Wealth and Resource Revenues – Countries such as Nigeria, Angola, and Botswana have established sovereign wealth funds to channel oil and mineral wealth into long-term investments. Though small compared to giants like Norway or Singapore, these funds represent efforts to transform natural resource revenues into intergenerational assets.

- Private Capital – Domestic entrepreneurs, pension funds, and regional investors now represent a growing financial force. African pension funds alone manage hundreds of billions, though most remain locked within national borders.

- Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) – The darker side of Africa’s capital story. Over USD 80 billion is estimated to leave Africa annually through trade misinvoicing, tax evasion, and other illicit channels. These flows highlight how Africa generates vast resources, but struggles to retain and channel them into productive development.

Together, these flows reshape Africa’s financial balance sheet. The challenge lies not in discovering resources but in mobilizing and managing them effectively.

1.3 Remittances as Africa’s Financial Backbone

Of all these flows, remittances stand out as Africa’s most significant — and underappreciated — source of external finance.

According to IFAD (2023), remittances to Africa totaled more than USD 95 billion in 2023, a figure projected to rise even further in 2024. The Institute for Security Studies (ISS, 2025) confirms that Nigeria alone receives over USD 20 billion annually, while countries such as Egypt and Kenya also rely heavily on diaspora transfers.

What makes remittances extraordinary is their resilience. Even during global economic downturns, they remain stable or grow, cushioning households against shocks more effectively than aid or investment (World Bank, 2024).

Remittances now outperform both FDI and aid combined, making them Africa’s true financial backbone. Yet, paradoxically, they remain one of the least leveraged for systemic development impact.

1.4 Country Case Studies – The Silent Giant at Work

- Nigeria: With inflows above USD 20 billion annually, diaspora remittances rival oil revenues in some years. Yet most are absorbed into household consumption due to limited financial instruments (GFRID, 2025).

- Egypt: Among the world’s top remittance recipients, Egypt consistently channels tens of billions into its economy, supplementing revenues from the Suez Canal.

- Kenya: Remittances now surpass tea and coffee exports as the country’s leading source of foreign exchange, illustrating their growing macroeconomic role.

These examples demonstrate the paradox of remittances: they are vast, reliable, and growing, yet remain underutilized as engines of structured development.

1.5 The Cost of Sending Money Home

Despite their scale, remittances to Africa face one major barrier: high transfer costs.

The United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Africa (UN OSAA, 2024) notes that Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest remittance costs in the world, averaging over 8 percent per transaction — compared to a global average of 6 percent, and well above the SDG target of 3 percent.

This inefficiency drains billions annually into fees rather than productive use. Structural issues such as lack of competition, limited access to banking, and restrictive regulatory frameworks are the main drivers. Lowering costs, therefore, is not simply about convenience — it is about releasing billions of dollars back into African households and economies.

1.6 Why Remittances Remain Underleveraged

Three structural issues prevent Africa from fully harnessing remittances:

- Consumption-driven flows – Remittances are primarily used for immediate needs (education, health, food), leaving little for long-term investment (IFAD, 2023).

- Lack of financial instruments – Few African countries have developed diaspora bonds, investment vehicles, or matched savings products that could channel remittances into productive projects (ISS, 2025).

- Trust and governance gaps – Migrants often hesitate to invest through official channels due to fears of corruption, mismanagement, and currency volatility.

Without addressing these barriers, remittances risk remaining a missed development opportunity.

1.7 The Missed Opportunity – Structural Barriers

Beyond remittances, Africa’s broader financial awakening is constrained by systemic weaknesses:

- Financial exclusion – Rural communities often lack formal banking, limiting investment capture.

- Fragmented markets – Africa’s 54 countries operate largely in silos, hindering cross-border capital flows.

- Currency volatility – The depreciation of the naira, cedi, and rand undermines investor confidence and diaspora trust.

- Illicit financial flows – Annual losses exceeding USD 80 billion undermine formal financial systems (ISS, 2025).

These barriers explain why Africa’s capital abundance has not yet translated into widespread prosperity.

1.8 Africa’s Awakening – Toward Financial Sovereignty

Despite the challenges, signs of a financial awakening are clear. Policymakers, institutions, and innovators are beginning to mobilize Africa’s hidden billions more strategically.

- Diaspora Bonds: Countries like Nigeria and Ethiopia have experimented with diaspora bonds, demonstrating both the potential and pitfalls of such instruments. Properly structured, they could unlock billions.

- Regional Financial Markets: Initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the African Exchanges Linkage Project aim to integrate fragmented markets, reduce transaction costs, and increase capital mobility.

- Digital Transformation: Mobile money and fintech are revolutionizing remittances, reducing costs, and expanding financial inclusion. Platforms like M-Pesa in Kenya are showing the way forward.

- Governance Reforms: Growing recognition that transparency and accountability are essential if Africa is to mobilize diaspora and domestic capital effectively.

The Global Forum on Remittances & Development (2025) projects that remittances to Africa will surpass USD 100 billion in 2024 — not just a financial milestone but a signal of Africa’s emerging role in global capital markets.

1.9 Conclusion – From Hidden to Harnessed Billions

Africa’s wealth awakening lies not in discovering new resources but in recognizing and mobilizing the ones already in its hands. Remittances — at USD 95 billion in 2023 and rising — symbolize this awakening. They already outpace aid and FDI, sustain households, and prove resilient in times of crisis. Yet, unless barriers are dismantled and instruments developed, they risk remaining an underutilized lifeline rather than a transformative engine.

The choice before Africa is clear. It can continue to allow billions to dissipate in inefficiency, mistrust, and illicit flows, or it can take bold steps toward financial sovereignty. By lowering costs, building instruments, integrating markets, and strengthening governance, Africa can transform hidden billions into sustainable engines of growth.

The awakening has begun. The question is whether Africa will harness it — or allow others to control its flows for another generation.

Part 2: Remittances — The Silent Giant

The most reliable source of Africa’s external finance is not aid or investment, but the billions sent quietly home each year by its diaspora.

2.1 Introduction – The Giant That Speaks Softly

Remittances are the quiet force sustaining Africa’s economies. While foreign aid attracts headlines and foreign direct investment (FDI) captures policy attention, the diaspora’s steady transfers have grown into Africa’s most reliable and consistent capital inflow. According to the Africa Finance Corporation (2025), the continent received over USD 95 billion in remittances in 2024, a figure almost equal to FDI. This quiet river of capital supports millions of households, stabilizes currencies, and increasingly rivals traditional sources of development finance.

Yet, despite their scale, remittances are systemically overlooked in economic planning. They are framed as private transfers rather than strategic flows — a blind spot that leaves one of Africa’s strongest financial engines underutilized.

2.2 Remittances by the Numbers

The scale of remittances underscores their importance.

- The Africa Finance Corporation (2025) reports inflows of USD 95 billion in 2024, with Nigeria and Egypt leading the way.

- Arise News (2025) highlights that these two countries alone account for more than half of the total inflows.

- According to Dabafinance (2025), other major recipients include Kenya, Ghana, Morocco, and Senegal, each receiving billions annually.

- Remittances are now larger than aid flows to the continent and nearly match FDI, making them indispensable to Africa’s financial stability.

Unlike FDI, which is volatile and tied to global market cycles, remittances have proven remarkably stable, even during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (ISS, 2025).

2.3 The Role in Sustaining Households

Remittances are not abstract flows. They are lifelines. The Institute for Security Studies (2025) emphasizes that remittances sustain millions of African households, financing education, healthcare, food security, and small businesses. Unlike foreign aid, which is filtered through governments and institutions, diaspora transfers go directly to families — bypassing bureaucracy and ensuring immediate impact.

In this way, remittances embody a form of bottom-up development finance. They empower households to make choices, reduce poverty, and build resilience. Research shows that children in remittance-receiving households are more likely to remain in school, while health outcomes improve significantly when families can afford basic services.

2.4 Beyond Consumption – Toward Employment and Growth

A common critique is that remittances are largely consumed rather than invested. While this is partially true, recent evidence suggests their impact goes further. Adigun (2025) finds that both remittances and FDI are key drivers of employment in Africa, though remittances are more evenly distributed across households and regions.

Remittances finance small-scale entrepreneurship, from corner shops to agricultural ventures, that rarely appear in macroeconomic statistics but cumulatively represent a vital segment of Africa’s employment base. They also serve as informal insurance systems, cushioning families during economic downturns or political instability.

The real opportunity lies in channeling a larger share into structured investment vehicles, such as diaspora bonds, SME financing schemes, and green energy projects.

2.5 Country Dynamics – Nigeria, Egypt, and Kenya

- Nigeria: The largest remittance recipient in Africa, consistently attracting USD 20–25 billion annually. Inflows often exceed oil revenues, underscoring their systemic importance (Arise News, 2025). However, weak financial instruments mean much of this capital is consumed rather than invested.

- Egypt: Ranking among the world’s top five remittance recipients, Egypt’s inflows exceed USD 30 billion annually, supplementing state revenues from the Suez Canal and tourism.

- Kenya: Remittances now surpass tea, coffee, and horticulture exports, making them the country’s largest source of foreign exchange (Dabafinance, 2025).

These cases illustrate a paradox: remittances are massive at the macro level, but their development potential is often untapped.

2.6 Why Remittances Outperform FDI and Aid

Remittances enjoy three structural advantages over other financial flows:

- Stability – Unlike aid, which depends on donor cycles, or FDI, which fluctuates with market conditions, remittances remain steady. Even during global recessions, migrants prioritize supporting their families (ISS, 2025).

- Direct Impact – Aid and FDI often move through governments and corporations, with leakages along the way. Remittances reach households directly, creating immediate economic effects.

- Resilience – Remittances respond quickly to crises. During natural disasters or pandemics, diaspora inflows typically increase, acting as shock absorbers for vulnerable households.

In short, remittances are Africa’s most resilient form of capital, though still underrecognized in policy frameworks.

2.7 Barriers to Unlocking the Giant

Despite their size, remittances face systemic challenges that limit their transformative potential:

- High transfer costs – Average costs in Sub-Saharan Africa remain above 8 percent, significantly higher than the SDG target of 3 percent.

- Limited investment channels – Few countries offer diaspora bonds or targeted investment schemes to capture remittances for development projects.

- Trust deficits – Migrants are often reluctant to invest through official systems due to governance concerns and currency volatility.

- Fragmented markets – Regulatory diversity across 54 African states hinders efficient regional remittance corridors.

Until these issues are addressed, remittances will remain primarily a household stabilizer rather than a continental growth driver.

2.8 The Untapped Potential of Diaspora Capital

The African diaspora represents not just billions in remittances but also vast intellectual and professional capital. Harnessing this requires a shift in policy thinking:

- Diaspora Bonds: Countries like Nigeria and Ethiopia have experimented with such instruments. While outcomes have been mixed, proper design could mobilize billions for infrastructure and climate adaptation.

- Diaspora Investment Funds: Pooled funds targeted at SMEs, housing, or healthcare could provide structured avenues for investment.

- Fintech Innovation: Digital platforms are already lowering costs and broadening access. Scaling them could accelerate financial inclusion and formal investment.

By building trust and offering credible instruments, African states could transform remittances from consumption into long-term development finance.

2.9 Remittances and the Future of Africa’s Financial Sovereignty

The rise of remittances marks a turning point in Africa’s financial awakening. At nearly USD 100 billion annually, they now rival FDI and dwarf aid, positioning Africa not as a passive recipient but as an active player in global finance.

The challenge is no longer about scale but about strategy. If governments, financial institutions, and regional bodies can create instruments that channel even a fraction of remittances into productive investment, the impact would be transformative — financing infrastructure, renewable energy, and industrialization.

As the ISS (2025) observes, remittances are more than household support: they are Africa’s silent giant, waiting to be mobilized as the engine of financial sovereignty.

2.10 Conclusion – Giving the Silent Giant a Voice

Remittances are no longer the overlooked billions. They are Africa’s largest and most resilient inflow, sustaining households and rivaling traditional sources of finance. Yet they remain underleveraged, trapped in a cycle of consumption due to high costs, weak instruments, and governance gaps.

The silent giant must be given a voice. By lowering transaction costs, building trust, and designing credible financial instruments, Africa can unlock remittances as a strategic driver of growth. In doing so, the continent would not only empower its households but also strengthen its sovereignty in global capital markets.

The diaspora is already sending billions. The question is whether Africa will build the systems to harness them.

Part 3: Sovereign Wealth and Resource Revenues

Africa’s sovereign wealth funds are more than savings accounts; they are strategic tools that could convert finite resources into intergenerational prosperity — if governance keeps pace with ambition.

3.1 Introduction – From Resource Windfalls to Long-Term Wealth

For decades, Africa’s natural resource revenues — oil, gas, diamonds, copper, cobalt — have been described as a blessing and a curse. Vast windfalls flowed into state coffers during boom cycles, only to evaporate during busts. Economists coined the term “resource curse” to describe the paradox of resource-rich states with fragile economies.

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) have been Africa’s answer to this dilemma: financial instruments designed to capture resource revenues and reinvest them into diversified, long-term portfolios. The International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF, 2023) notes that more than 20 African countries have either operational SWFs or plans to establish them. Together, these funds manage an estimated USD 100 billion, still modest by global standards but growing rapidly.

Africa’s SWFs are not yet in the league of Norway’s USD 1.5 trillion Government Pension Fund Global or Singapore’s Temasek, but they symbolize a shift: the recognition that resource revenues must be saved, invested, and leveraged strategically for development.

3.2 The Rationale for Sovereign Wealth in Africa

The logic for SWFs in Africa is threefold:

- Stabilization – To shield national budgets from commodity price volatility. Oil-dependent states such as Nigeria and Angola use SWFs to smooth expenditure during downturns.

- Savings for Future Generations – To ensure that finite resources like oil or diamonds benefit not only current citizens but also future generations.

- Strategic Investment – To channel revenues into infrastructure, education, green energy, or foreign investments that diversify economies beyond raw commodities.

As the Wilson Center (2025) observes, African SWFs are increasingly experimenting with innovative mandates, from climate finance to impact investment — a sign of the continent’s determination to turn short-term resource rents into transformative capital.

3.3 Botswana’s Pula Fund – A Benchmark Case

Botswana’s Pula Fund remains the continent’s most frequently cited SWF success story. Established in 1994 and funded primarily by diamond revenues, the fund has become a model of prudent financial management.

According to the Bank of Botswana (2024), the Pula Fund is invested in global equities and bonds, with rules that limit withdrawals to protect intergenerational equity. The IMF (2023) commended Botswana’s framework, noting that while challenges remain, the fund has shielded the economy from external shocks and maintained macroeconomic stability.

Botlhale (2024) highlights that the Pula Fund demonstrates how resource revenues can be transformed into sustainable growth drivers. By resisting political pressure to overspend during boom years, Botswana avoided the worst of the resource curse.

However, even Botswana’s model is not without challenges. Returns fluctuate with global markets, and questions remain about how to balance foreign investments with domestic development needs.

3.4 Nigeria and Angola – Struggles of Oil Giants

Nigeria and Angola, Africa’s largest oil exporters, also established SWFs, but with mixed outcomes.

- Nigeria: The Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA), created in 2011, manages stabilization, infrastructure, and future generations funds. Despite billions in assets, political interference and frequent withdrawals for short-term budget needs have undermined its growth.

- Angola: The Fundo Soberano de Angola was launched with fanfare in 2012 but became mired in allegations of mismanagement and corruption, illustrating the risks when governance frameworks lag behind financial ambition.

These examples underscore that while SWFs hold promise, governance, transparency, and fiscal discipline determine their success.

3.5 The Global Context – Learning from Giants

Globally, SWFs have become powerhouses of capital. Norway’s Oil Fund is worth more than 3 times Norway’s GDP; Singapore’s Temasek is a major global investor in technology and infrastructure. These funds illustrate what Africa’s SWFs aspire to: diversification, scale, and global influence.

The IFSWF (2023) stresses that African funds are at an early stage, often managing portfolios below USD 10 billion. To achieve scale, they will need to pool resources, attract professional management, and insulate funds from political cycles.

The comparison highlights both potential and peril. Africa has the raw material revenues, but without discipline, its funds risk becoming piggybanks for short-term politics rather than vehicles for long-term prosperity.

3.6 Innovation – Africa’s Distinct Approach

Unlike traditional stabilization-only funds, African SWFs are experimenting with broader mandates. The Wilson Center (2025) notes several trends:

- Development Mandates: Funds investing directly in domestic infrastructure, agriculture, and renewable energy rather than solely in foreign bonds.

- Climate and Green Investment: Some funds are allocating resources to renewable energy and climate adaptation, aligning with Africa’s vulnerability to climate change.

- Regional Cooperation: Proposals to pool smaller funds into regional vehicles that could achieve greater scale and bargaining power in global markets.

This innovative landscape suggests Africa may chart its own path in the SWF space, blending stabilization with development financing.

3.7 The Risks – Corruption, Volatility, and Governance

The potential of SWFs is enormous, but so are the risks:

- Corruption: Mismanagement in Angola illustrates how SWFs can become vehicles for elite enrichment rather than national savings.

- Volatility: Funds remain heavily dependent on resource exports. Oil price collapses can quickly drain assets.

- Political Interference: Frequent withdrawals to plug budget deficits undermine long-term savings goals.

- Capacity Constraints: Many funds lack professional asset management teams, reducing returns.

As Botlhale (2024) cautions, without strong legal frameworks, oversight, and independence, SWFs can exacerbate the resource curse rather than cure it.

3.8 Toward Financial Sovereignty – A Way Forward

To realize their potential, Africa’s SWFs must embrace reforms and innovation:

- Strengthening Governance – Insulate funds from political cycles, enforce transparency, and adopt international best practices such as the Santiago Principles (IFSWF, 2023).

- Diversification – Invest beyond oil and gas, targeting technology, agriculture, healthcare, and renewable energy.

- Regional Models – Pool smaller funds into regional SWFs that can achieve scale and reduce duplication.

- Linking to Development Goals – Align SWF investments with national priorities such as infrastructure, education, and climate resilience.

The Wilson Center (2025) argues that SWFs can become “sovereign development funds,” driving structural transformation rather than merely saving resource rents.

3.9 Conclusion – Africa’s Resource Future

Africa’s sovereign wealth funds symbolize both the continent’s greatest opportunities and its sharpest dilemmas. With over USD 100 billion in assets and growing, they could transform finite oil and mineral revenues into intergenerational prosperity. The Pula Fund in Botswana demonstrates what is possible with discipline, while Nigeria and Angola illustrate the dangers of weak governance.

The future of African SWFs hinges on one question: will they serve as strategic engines of transformation or remain fragile savings pots vulnerable to politics and corruption?

If Africa gets it right, sovereign wealth could become the financial foundation of its economic awakening — converting resource wealth into resilient, diversified, and future-ready economies. If it fails, the curse of squandered abundance may persist for another generation.

Part 4: Global Investors and Africa’s Allure

As Africa attracts record levels of foreign investment, global powers see not just profits but influence. The continent’s resources, markets, and demographics make it the frontier of 21st-century capital competition.

4.1 Introduction – Africa as the New Investment Frontier

The year 2024 marked a historic milestone: foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa surged to USD 97 billion, a 75 percent increase from the previous year, according to UNCTAD (2025) and Further Africa (2025). This dramatic rise reflects more than capital chasing returns — it signals Africa’s emergence as one of the world’s most dynamic investment frontiers.

Global investors are drawn by three interlocking factors: demographics, resources, and markets. Africa has the world’s fastest-growing population, a median age under 20, and rapidly expanding urban centers. It is home to vast reserves of strategic minerals — cobalt, lithium, platinum, oil, and gas — critical for the global energy transition. And its consumer markets are projected to exceed USD 2.5 trillion by 2030.

No longer a marginal destination, Africa is now at the center of competing global investment strategies, where economics and geopolitics intertwine.

4.2 The Surge in Foreign Direct Investment

The numbers tell a compelling story.

- UNCTAD (2025) reports that FDI inflows reached USD 97 billion in 2024, up from USD 55 billion in 2023 — the fastest growth of any region globally.

- This surge comes despite global headwinds, underscoring investor confidence in Africa’s resilience.

- The EY Africa Attractiveness Report (2024) highlights Africa’s strong performance in sectors such as renewable energy, digital infrastructure, and fintech, which are attracting increasing private equity and venture capital interest.

- UNCTAD’s earlier World Investment Report (2023) had already noted Africa’s resilience, projecting that the continent would outperform other developing regions. The 2024 results confirm that prediction.

This boom underscores that Africa is not just surviving global uncertainty but actively reconfiguring global capital flows.

4.3 Who Invests in Africa – The Changing Landscape

Conventional wisdom holds that China dominates African investment. While Beijing is indeed a critical player, the reality is more complex.

According to ODI (2025), the largest foreign investors in Africa are not China but European states and the United States. Collectively, Western investors hold the largest stock of accumulated investments, particularly in extractives, financial services, and infrastructure.

- Europe remains Africa’s largest investor, leveraging historical ties and proximity.

- The United States is increasingly active in technology, energy, and finance, with growing private equity activity in fintech hubs like Lagos, Nairobi, and Cape Town.

- China continues to dominate infrastructure, energy, and mining, especially through state-owned enterprises and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects.

- Gulf States (notably the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia) are rapidly scaling investments in agribusiness, ports, and renewable energy, positioning themselves as strategic food and logistics partners.

This multipolar investment landscape illustrates that Africa is no longer tied to a single dominant external power but is instead a stage of competitive global engagement.

4.4 Sectoral Shifts – From Oil to Green and Digital

The composition of FDI in Africa is evolving. While extractives remain important, new sectors are driving growth:

- Green Energy – Africa’s solar and wind potential is among the highest in the world. Global investors are pouring capital into large-scale renewable projects in Egypt, Morocco, Kenya, and South Africa.

- Critical Minerals – With rising global demand for electric vehicle batteries, cobalt (DRC), lithium (Zimbabwe), and rare earths are attracting billions in mining investment.

- Digital Economy – Africa’s fintech revolution has become a magnet for venture capital. Lagos, Nairobi, and Cape Town now rank among the world’s fastest-growing tech hubs (EY, 2024).

- Agribusiness – Gulf investors, in particular, are securing long-term food supply through large-scale land and agribusiness investments across East and West Africa.

This diversification reflects a continent that is no longer viewed solely as a source of raw commodities but as a market for innovation and future growth.

4.5 Investment as Diplomacy – Geopolitical Undertones

Investment in Africa is never purely financial. It is geopolitical.

- China’s BRI projects are not only about infrastructure but also about cementing influence, securing access to resources, and building long-term political alliances.

- U.S. and European investment strategies often emphasize governance, ESG standards, and partnerships with private enterprise — part of broader diplomatic competition with China.

- Gulf states use investment to secure strategic food and energy corridors, while also projecting soft power through philanthropy and culture.

As UNCTAD (2025) notes, Africa’s investment surge is reshaping not just balance sheets but also the global political economy, where capital serves as both currency and diplomacy.

4.6 Risks and Realities – The Fragility of FDI

Despite record inflows, FDI in Africa carries risks:

- Volatility: Global recessions, commodity price swings, or interest rate shocks can reduce inflows sharply.

- Concentration: FDI remains heavily concentrated in a few countries (Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Morocco) and a few sectors (extractives, energy, telecoms).

- Debt Traps: Infrastructure loans tied to FDI can lead to unsustainable debt, particularly with state-driven Chinese financing.

- Political Instability: Coups, civil conflict, and governance deficits in parts of Africa deter long-term investment.

The EY (2024) report warns that without reforms in governance and regional integration, Africa risks losing momentum despite its demographic and market advantages.

4.7 Toward an African Investment Strategy

The surge in foreign capital is an opportunity but also a challenge. To harness it, Africa must shape investment flows rather than merely receive them. Strategies include:

- Regional Integration – The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides a framework for harmonizing regulations, reducing barriers, and attracting investment at scale.

- African Credit Rating Agency – To reduce dependence on Western agencies that often underrate African economies, raising borrowing costs.

- Domestic Resource Mobilization – Combining remittances, sovereign wealth funds, and domestic pension funds with FDI to reduce vulnerability to external shocks.

- Investment in Human Capital – Aligning FDI with skills development to ensure Africa’s youth benefit directly from global investment.

As UNCTAD (2023) argues, Africa must position itself not as a passive host but as a co-shaper of global investment flows.

4.8 Conclusion – The Allure of Africa

Africa’s allure lies in more than its natural resources. It is in its people, its markets, and its future. The continent’s record USD 97 billion in FDI inflows in 2024 proves that investors see not only risks but opportunities. Yet the strategic question remains: will Africa channel this capital toward inclusive development, or will it reproduce patterns of extraction and dependency?

The competition among China, the West, and the Gulf underscores that Africa has leverage. But leverage only matters if used wisely. By shaping investment flows with clear strategies, Africa can turn allure into agency — ensuring that global investors do not just see Africa as a prize to be won, but as a partner in building the 21st-century economy.

Read also: Exposing The Untold Truth By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Part 5: Risks, Volatility, and Capital Flight

Africa generates billions in wealth each year, but almost as quickly as capital arrives, vast sums escape through illicit flows, debt vulnerabilities, and currency crises — eroding the foundations of growth and sovereignty.

5.1 Introduction – The Paradox of Plenty and Loss

Africa’s financial awakening is undeniable. Record remittances, sovereign wealth initiatives, and rising foreign investment flows suggest a continent on the rise. Yet behind these headlines lies a sobering paradox: Africa continues to hemorrhage vast amounts of wealth through illicit financial flows (IFFs), capital flight, and macroeconomic volatility.

The UNCTAD and Africa-Europe Foundation (2023) estimate that Africa loses USD 88.6 billion annually to illicit flows — money that could have financed infrastructure, healthcare, or education. The UNODC (2025) stresses that these outflows are not abstract numbers but structural drains that weaken state capacity, undermine development, and perpetuate dependency on external finance.

Thus, Africa’s challenge is twofold: not only to attract capital but to retain and harness it.

5.2 The Scale of Illicit Financial Flows

Illicit financial flows represent the single greatest leakage of Africa’s wealth.

- UNCTAD & AEF (2023) put annual losses at nearly USD 90 billion, equivalent to 3.7 percent of Africa’s GDP.

- These flows include tax evasion, trade misinvoicing, smuggling, corruption, and criminal networks siphoning resources offshore.

- African Business (2025) emphasizes that weak financial systems and porous borders make Africa particularly vulnerable to criminal exploitation, exacerbating capital loss.

The scale of these outflows dwarfs aid inflows and undermines sovereign control over financial resources.

5.3 The Mechanics of Capital Flight

Illicit financial flows occur through multiple channels:

- Trade Misinvoicing – Corporations deliberately underreport exports or inflate imports to shift profits offshore, draining billions from African treasuries.

- Tax Avoidance and Evasion – Multinational corporations exploit loopholes and secrecy jurisdictions to avoid paying taxes on African operations.

- Corruption and Kleptocracy – Public officials embezzle state revenues, transferring funds into foreign accounts.

- Criminal Networks – Smuggling of minerals, wildlife, and narcotics generates shadow capital that flows outside legitimate systems (UNODC, 2025).

These mechanisms make Africa’s financial system leaky by design, with powerful actors often complicit.

5.4 The Human and Development Cost

Every dollar lost to IFFs is a dollar not spent on development.

- Carnegie Endowment (2024) highlights that tax evasion alone robs governments of revenues needed to build schools, hospitals, and infrastructure.

- The annual losses of USD 88.6 billion could cover Africa’s financing gap for universal primary education or significantly fund climate adaptation.

- Worse, capital flight deepens inequality, as elites externalize wealth while ordinary citizens face underfunded public services.

Illicit flows thus perpetuate Africa’s dependence on aid and external borrowing, reinforcing a cycle of vulnerability.

5.5 Volatility and Debt Risks

Beyond IFFs, Africa faces volatility from debt and currency crises.

- Several African states remain highly indebted, with external shocks exacerbating vulnerabilities.

- Currency depreciation, such as the collapse of the Nigerian naira and Ghanaian cedi in recent years, erodes investor confidence and drains remittance value.

- External capital, whether in the form of loans or portfolio flows, can exit as quickly as it arrives, destabilizing economies.

The Reuters (2024) report on Nigeria’s plan to launch a USD 10 billion diaspora fund illustrates an effort to counter these vulnerabilities by mobilizing internal capital. Yet such strategies must be coupled with strong safeguards to avoid repeating cycles of mismanagement.

5.6 Africa’s Vulnerability to Criminal and Shadow Economies

The African Business (2025) report warns that Africa’s vulnerability to criminal exploitation is rising. Gold smuggling from Sudan, arms trafficking in the Sahel, and narcotics through West African ports all feed illicit capital flows. These shadow economies not only drain revenue but also finance insurgency, conflict, and governance breakdowns.

This posits that illicit flows are not just financial issues but security threats, undermining states from within.

5.7 Strategies for Combating Illicit Flows

Despite the scale of the challenge, African states are not powerless. Carnegie (2024) and UNODC (2025) outline several strategic responses:

- Tax Reforms and Transparency – Strengthen revenue systems, adopt digital tax tracking, and close loopholes exploited by multinationals.

- Trade Oversight – Implement better monitoring of import/export data to curb misinvoicing.

- International Cooperation – Collaborate with global financial centers to trace and repatriate stolen assets.

- Regional Institutions – Establish African-led mechanisms for financial intelligence and enforcement.

- Diaspora Engagement – Instruments such as Nigeria’s proposed USD 10 billion diaspora fund (Reuters, 2024) could help redirect legitimate flows into productive channels.

The challenge is not technical capacity alone, but political will.

5.8 Currency Crises and Investor Confidence

Volatility in African currencies amplifies risks of capital flight.

- Nigeria’s naira crisis illustrates how currency depreciation erodes remittance value, fuels inflation, and undermines trust in the financial system.

- Similarly, depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi and volatility of the South African rand have shaken investor confidence.

- Currency weakness incentivizes elites to move wealth offshore, reinforcing the cycle of capital flight.

Stabilizing currencies through sound macroeconomic management and diversified exports is therefore critical to retaining capital.

5.9 Toward Retention and Resilience

The way forward requires a paradigm shift: Africa must focus not only on attracting capital but on retaining and multiplying it. Key steps include:

- Building robust sovereign wealth funds insulated from political interference.

- Deepening regional financial markets to offer secure African investment alternatives.

- Leveraging diaspora funds as credible, well-managed instruments for long-term financing.

- Establishing an African Credit Rating Agency to reduce reliance on external perceptions that raise borrowing costs.

Most importantly, tackling illicit flows demands aligning financial governance with broader goals of transparency, accountability, and security.

5.10 Conclusion – Plugging the Leaks to Build Sovereignty

Africa’s greatest financial challenge is not scarcity but leakage. The continent loses nearly USD 90 billion annually to illicit flows, faces recurring currency crises, and remains exposed to debt vulnerabilities. These losses undermine the very capital inflows celebrated in earlier sections — remittances, FDI, and sovereign wealth initiatives.

As the UNODC (2025) stresses, curbing illicit flows is not simply a financial reform but a development imperative. Without plugging the leaks, Africa’s hidden billions will remain shadows, financing elites and criminals rather than citizens and communities.

The task is clear: Africa must defend its wealth as fiercely as it seeks to attract it. Only by retaining capital can the continent turn financial awakening into financial sovereignty.

Part 6: Toward Financial Sovereignty

Africa’s journey from hidden billions to financial sovereignty requires more than inflows; it demands control, innovation, and trust. The diaspora may hold the key.

6.1 Introduction – The Meaning of Financial Sovereignty

Financial sovereignty is more than economic jargon; it is the foundation of political and developmental independence. For Africa, it means the capacity to finance its priorities with its own resources, to insulate itself from the volatility of global capital markets, and to shape investment flows in ways aligned with its vision.

Throughout history, Africa has been defined by financial dependency. Aid, concessional loans, and foreign direct investment (FDI) have dominated discourse, often reinforcing asymmetric relationships with the Global North. But as remittances, sovereign wealth initiatives, and foreign investments expand, the conversation is shifting. The question is no longer simply how to attract capital, but how to control it, retain it, and deploy it strategically.

This final section of the dossier explores the pathways toward African financial sovereignty, with a particular focus on diaspora bonds — one of the most innovative, yet underutilized, tools in Africa’s financial arsenal. Drawing on global lessons, African experiments, and forward-looking strategies, it argues that sovereignty is both possible and urgent.

6.2 Africa’s Dependence on External Capital – The Old Model

For decades, Africa’s development financing relied on external capital inflows, often dictated by donors, lenders, or investors with their own priorities. This dependency created systemic vulnerabilities:

- Aid Dependency – While essential for humanitarian crises, aid often entrenched cycles of reliance and donor-driven policies.

- Debt Burdens – External borrowing left many African countries trapped in debt-service spirals, with significant portions of national budgets consumed by repayments.

- FDI Volatility – While FDI surged to record highs in 2024 (UNCTAD, 2025), its flows are concentrated in a handful of sectors and countries, leaving others exposed to cycles of boom and bust.

- Currency Fragility – Reliance on foreign inflows left African economies vulnerable to currency crises, as seen in Nigeria’s naira or Ghana’s cedi.

The cumulative effect has been constrained sovereignty. Policies were shaped not by African priorities, but by the need to satisfy creditors, attract investors, or comply with donor conditions.

As the Brookings Institution (2022) argues, this model is unsustainable: Africa cannot achieve its long-term development ambitions while its financing remains externally determined. Sovereignty requires mobilizing African wealth — from remittances, savings, and resource revenues — and channeling it into African priorities.

6.3 The Case for Sovereignty – Why Control Matters Now

The urgency of financial sovereignty has never been greater. Several converging trends highlight why Africa must move beyond dependency:

- Demographic Explosion

Africa’s population will double by 2050, adding nearly 1 billion people. Financing jobs, infrastructure, and services for this surge cannot rely solely on external sources. Sovereignty ensures domestic resilience. - Geopolitical Competition

As highlighted in Part 4, Africa is the stage for competition between China, the U.S., Europe, and the Gulf. While this brings capital, it also risks new forms of dependency. Sovereignty means engaging these powers on Africa’s terms, not theirs. - Resource Transition

Africa holds key minerals for the global energy transition. Without financial sovereignty, the continent risks repeating the old pattern: resources extracted, wealth exported, development unrealized. - Resilience to Shocks

The COVID-19 pandemic and global inflation crisis underscored Africa’s vulnerability to external shocks. Sovereignty would allow Africa to cushion itself through endogenous financing mechanisms.

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI, 2025) puts it plainly: Africa must turn remittances and diaspora wealth into structured instruments that not only supplement external finance but gradually replace it. This is the heart of financial sovereignty.

6.4 Diaspora Bonds – The Sleeping Giant of Development Finance

Among the many instruments available to Africa in its quest for financial sovereignty, few are as promising — and as underutilized — as diaspora bonds.

Diaspora bonds are government-issued debt instruments targeted specifically at diaspora communities. Unlike traditional investors, diaspora populations are motivated not only by financial returns but also by a sense of patriotism, emotional attachment, and commitment to their homeland. This dual motivation provides governments with access to relatively patient capital, often at lower costs than international markets.

The Brookings Institution (2022) notes that diaspora bonds can serve three critical functions for Africa:

- Mobilizing Stable Capital – Diaspora investors are less likely to withdraw during crises, making bonds a reliable financing source.

- Reducing External Dependence – By tapping their own citizens abroad, African states reduce reliance on volatile international capital markets.

- Financing Development Priorities – Diaspora bonds can be earmarked for infrastructure, green energy, or education, ensuring direct alignment with development goals.

The African Leadership Magazine (2025) calls them “Africa’s new economic lifeline”, arguing that the continent’s 160 million-strong diaspora represents a reservoir of both capital and trust that has yet to be fully mobilized.

The Scale of Potential

The numbers are staggering. Africa’s diaspora sends home more than USD 95 billion annually in remittances (see Part 2). If even a fraction of this were channeled into structured diaspora bonds, it could rival aid and FDI as a development finance source. The ODI (2025) estimates that capturing just 5 percent of annual remittances into diaspora bonds could raise USD 5 billion annually — enough to fund significant infrastructure or climate adaptation programs.

Banking on Trust

Trust is the cornerstone of diaspora bonds. Unlike international investors, diasporas are often willing to overlook higher risks if they believe funds will genuinely benefit their homeland. As the OMFIF (2024) notes, diaspora investors bring not just money but also networks, skills, and a willingness to reinvest in local communities.

This “patriotic premium” has been demonstrated in other parts of the world, but Africa has only scratched the surface.

6.5 Lessons from Global Experiences

While Africa is just beginning to embrace diaspora bonds, other regions have shown what is possible — and what pitfalls must be avoided.

Israel – A Benchmark Case

Israel has been issuing diaspora bonds since the 1950s through the Development Corporation for Israel. These bonds have raised over USD 40 billion to fund infrastructure, housing, and defense. Their success rests on three pillars:

- Strong emotional ties between diaspora Jews and the homeland.

- Transparent financial management through a trusted intermediary.

- Flexible terms that appeal to different segments of the diaspora.

This case shows that diaspora bonds can become long-term, reliable financing vehicles when trust and institutional credibility are strong.

India – Tapping Diaspora in Times of Crisis

India successfully launched several diaspora bond programs, particularly during balance-of-payment crises. The Resurgent India Bonds (1998) raised USD 4.2 billion in just a few weeks, primarily from Indians abroad. The secret: high interest rates, combined with the diaspora’s desire to stabilize their homeland.

For Africa, the lesson is clear: diaspora bonds are not just patriotic instruments but can also serve as counter-cyclical tools during financial crises.

Nigeria and Ethiopia – Mixed Lessons

Africa has already tested the waters with diaspora bonds, though results are mixed.

- Nigeria launched a USD 300 million diaspora bond in 2017, oversubscribed by international investors, showing the potential for scaling. However, governance concerns limit future trust.

- Ethiopia attempted diaspora bonds for its Renaissance Dam but struggled to build credibility, as many in the diaspora feared mismanagement.

The Africa Report (2025) highlights Kenya’s debut diaspora bond as another milestone, noting five key lessons: clear communication, alignment with diaspora interests, transparent governance, competitive yields, and targeted use for visible projects.

Pitfalls to Avoid

From these experiences, three risks stand out for Africa:

- Governance Failures – Without transparency, diaspora bonds quickly lose credibility, as seen in Ethiopia’s early efforts.

- Uncompetitive Yields – If bonds don’t offer returns comparable to global options, even patriotic investors hesitate.

- Poor Marketing – Diaspora populations are diverse; successful bonds require tailored outreach and sustained communication.

As the ODI (2025) stresses, diaspora bonds are not automatic successes. They demand strong institutions, credible frameworks, and deliberate strategies to build diaspora trust.

6.6 Africa’s Early Experiments – Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Kenya

Nigeria – A Cautious Success Story

Nigeria remains the most prominent African case of diaspora bond issuance. In 2017, the government launched a USD 300 million diaspora bond, targeting Nigerians living abroad. The bond was oversubscribed, with strong participation from both diaspora investors and international institutions.

This experience demonstrated three key insights:

- Diaspora Appetite Exists – Nigerians abroad are willing to invest in their homeland if credible instruments are provided.

- Global Co-Investors Follow – The oversubscription indicated that diaspora bonds can attract not only migrants but also institutional investors seeking exposure to African assets.

- Scale is Achievable – If properly structured, bonds can raise hundreds of millions — potentially billions — in relatively short timeframes.

However, governance and transparency challenges remain. While the 2017 bond succeeded, critics argue that subsequent Nigerian bond proposals (including discussions of a USD 10 billion diaspora fund reported by Reuters (2024)) have been hindered by concerns over credibility and clarity of fund utilization.

Ethiopia – Lessons in Trust

Ethiopia attempted diaspora bonds twice, primarily to finance the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Despite the project’s symbolic value, uptake among the diaspora was disappointing. Many Ethiopian expatriates cited distrust in government financial management and concerns over corruption.

The Ethiopian case illustrates that patriotism alone is not enough. As the ODI (2025) emphasizes, emotional attachment must be matched by credible financial governance. Otherwise, diaspora communities may withhold participation, even for nation-building projects.

Kenya – A New Frontier

Kenya’s debut diaspora bond in 2025 was a bold move. According to The Africa Report (2025), the bond targeted infrastructure and social development, offering competitive yields and strong marketing campaigns in diaspora hubs like London, Washington D.C., and Dubai.

Five lessons emerged:

- Clear Communication – Diasporas must understand exactly how funds will be used.

- Competitive Returns – Kenya benchmarked yields to global markets, making the bonds attractive beyond patriotism.

- Transparency Mechanisms – Regular reporting reassured investors of accountability.

- Targeted Outreach – Engagement with diaspora associations increased trust and uptake.

- Symbolism and Identity – The bond was marketed not only as a financial tool but as a way for Kenyans abroad to “own a piece of home.”

Kenya’s effort is widely seen as a blueprint for other African states — combining emotional appeal with professional financial structuring.

6.7 Barriers and Pitfalls of Diaspora Bonds

While diaspora bonds hold enormous promise, several structural and psychological barriers must be confronted if Africa is to scale them effectively.

- Trust Deficits

The single greatest obstacle is trust. Many African diasporas have witnessed corruption, mismanagement, and political interference in their homelands. As African Leadership Magazine (2025) cautions, without transparency, diaspora bonds risk being dismissed as “another fundraising gimmick.”

Solutions include independent fund management, third-party audits, and ring-fencing funds for specific projects with visible outcomes.

- Weak Financial Infrastructure

Some African states lack the institutional frameworks to issue and manage bonds effectively. Diaspora bonds require strong regulatory systems, credit ratings, and professional asset managers — capacities are still uneven across the continent.

- Competitive Alternatives

Diaspora investors are also global investors. They compare returns in African bonds with global markets. If yields are unattractive or risks too high, they may invest elsewhere. As the OMFIF (2024) report stresses, patriotism provides a “premium,” but financial logic still matters.

- Fragmented Diaspora Populations

Africa’s diaspora is vast and diverse, spread across continents and shaped by varied experiences of migration. Mobilizing them requires tailored communication — what appeals to Nigerian professionals in London may not resonate with Kenyan entrepreneurs in Dubai.

- Political Risk and Currency Volatility

Diaspora investors remain wary of political instability and currency depreciation. A bond denominated in naira, cedi, or birr carries exchange-rate risks that can wipe out returns. Unless instruments are denominated in stable currencies (USD, EUR, GBP), uptake may remain limited.

- Marketing and Awareness Gaps

Many potential diaspora investors are simply unaware of bond opportunities. Governments often fail to mount sustained campaigns in key diaspora hubs. In contrast, Israel and India succeeded by institutionalizing diaspora outreach, creating long-term bonds of trust.

Overcoming the Pitfalls

To overcome these barriers, Africa must innovate:

- Regional Approaches: Instead of fragmented national efforts, pooled Pan-African diaspora bonds could reduce risk and increase scale.

- Technology Integration: Using fintech platforms to simplify diaspora bond purchases could lower costs and increase accessibility.

- Diaspora Inclusion in Governance: Giving diaspora representatives a seat at the table in bond management structures can build ownership and trust.

- Visible Impact: Linking diaspora funds to visible projects — a hospital, a solar farm, a school — strengthens emotional engagement and demonstrates results.

As the ODI (2025) concludes, diaspora bonds are not merely financial instruments; they are trust contracts between states and their citizens abroad. Without credibility, they fail. With credibility, they can transform Africa’s financial landscape.

6.8 Toward Regional Instruments – Pan-African Bonds and Markets

The story of diaspora bonds is not only national but also regional. Africa’s financial sovereignty requires scale, and scale is best achieved when countries pool resources rather than pursue fragmented strategies.

The Logic of Regionalization

Individually, many African states face credibility gaps, governance concerns, and limited diaspora pools. Collectively, however, the continent’s 160 million diaspora members represent a formidable capital base. If coordinated through regional mechanisms, diaspora bonds could raise billions annually while spreading risk.

As ODI (2025) notes, diaspora finance should not be seen merely as a series of scattered national initiatives but as part of a continental architecture for self-financing development.

Pan-African Diaspora Bonds

Imagine an African Union–backed diaspora bond, marketed across global financial hubs. Backed by multiple governments, managed by professional custodians, and tied to high-impact projects (infrastructure, climate adaptation, digital transformation), such bonds could:

- Reduce individual country risk by pooling credibility.

- Offer diaspora investors diversified exposure across Africa.

- Achieve scale that individual states cannot match.

The African Leadership Magazine (2025) suggests that regional diaspora instruments could also strengthen African integration, giving diasporas a role in building the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and transnational infrastructure corridors.

Building Regional Financial Markets

Beyond bonds, Africa needs deep and liquid regional capital markets. Currently, Africa’s 54 fragmented markets lack integration, limiting investor confidence and liquidity. A regionalized approach — such as the African Exchanges Linkage Project — could provide platforms for diaspora bonds, green bonds, and infrastructure securities, traded across borders with unified standards.

As OMFIF (2024) emphasizes, banking on the diaspora means creating not just instruments but ecosystems that allow capital to flow seamlessly across Africa.

6.9 Beyond Bonds – The Architecture of African Financial Sovereignty

Diaspora bonds are a powerful tool, but they are only one pillar of Africa’s broader financial sovereignty project. Sovereignty requires a comprehensive architecture — a re-engineering of how Africa mobilizes, retains, and deploys capital.

- Mobilizing Domestic Capital

Africa sits on vast untapped domestic savings. Pension funds, insurance pools, and sovereign wealth funds collectively hold hundreds of billions of dollars. Yet much of this capital is invested in low-yield foreign assets or remains locked in illiquid domestic markets.

Financial sovereignty means redirecting these funds into Africa’s own infrastructure, technology, and green energy sectors — with safeguards to protect returns and reduce political interference.

- Harnessing Remittances Beyond Bonds

Remittances, exceeding USD 95 billion annually, should not only fund household consumption. Governments and financial institutions must create products such as:

- Remittance-backed securities to pool diaspora transfers into development finance.

- Matched savings schemes, where governments or banks co-invest alongside diaspora remittances.

- Diaspora equity funds, offering partial ownership in African SMEs or infrastructure.

As Brookings (2022) and ODI (2025) argue, bonds are the entry point, but broader diaspora finance requires innovation in instruments.

- Building African Credit Infrastructure

A persistent barrier to African finance is external credit ratings. Western agencies often underrate African economies, inflating borrowing costs. Sovereignty demands the creation of an African Credit Rating Agency that reflects Africa’s realities while maintaining global credibility.

- Curbing Illicit Financial Flows

As explored in Part 5, Africa loses nearly USD 90 billion annually to illicit financial flows. Sovereignty requires plugging these leaks through stronger tax regimes, trade oversight, and international cooperation. Without stopping outflows, inflows alone will never suffice.

- Digital Transformation of Finance

Fintech is Africa’s financial revolution. Platforms like M-Pesa in Kenya have already transformed payments. Extending this innovation into bond purchases, savings products, and regional trading platforms could democratize finance — making diaspora and domestic participation easier, faster, and cheaper.

- Aligning Finance with Development Priorities

Financial sovereignty is not about capital for its own sake. It is about alignment. Every dollar mobilized must serve Africa’s strategic priorities: infrastructure, industrialization, green energy, education, and healthcare. This requires robust planning and governance frameworks.

6.10 Conclusion – The Road to Self-Financing Africa

Africa stands at a crossroads. The continent’s hidden billions — remittances, sovereign wealth funds, diaspora finance — have been revealed throughout this dossier. The challenge is no longer whether Africa has resources but whether it has the will and architecture to control them.

Diaspora bonds exemplify the promise and pitfalls of sovereignty. Properly managed, they can channel patriotism into billions of dollars for transformation. Poorly managed, they risk becoming symbols of mistrust. The lessons are clear: transparency, trust, and innovation are non-negotiable.

But bonds alone are not enough. Sovereignty requires a whole-of-continent approach:

- Mobilizing domestic and diaspora capital.

- Building regional markets and institutions.

- Plugging the leaks of illicit flows.

- Harnessing digital transformation.

- Aligning finance with Africa’s long-term vision.

As the OMFIF (2024) and African Leadership Magazine (2025) both stress, the diaspora is not simply a source of money — it is Africa’s extended community, its ambassadors, its investors, and its future. Engaging them meaningfully is as much about identity as economics.

In the words of the ODI (2025), the journey from remittances to bonds is the journey from dependence to sovereignty. It is the transformation of Africa’s relationship with global finance — from recipient to architect.

The road will be long and difficult, requiring reforms, discipline, and vision. But the prize is clear: an Africa that finances itself, speaks with financial independence, and defines its destiny not by aid flows or foreign investors, but by the power of its people — at home and abroad.

Financial sovereignty is not a dream. It is a necessity. And the time to build it is now.

References

Adigun, G.T. (2025). Remittances and FDI: Drivers of employment in the African economy. Fiscal Studies Journal, 18(8), p.436. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1911-8074/18/8/436 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Africa Finance Corporation (2025). Africa received over USD 95bn in remittances in 2024, nearly matching FDI. Nairametrics. Available at: https://nairametrics.com/2025/06/26/africa-received-95-billion-in-remittances-in-2024-as-nigeria-egypt-led-inflows-afc-report/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

African Business (2025). Africa’s vulnerability to criminals spurs illicit financial flows. African Business Magazine. Available at: https://african.business/2025/07/finance-services/africas-vulnerability-to-criminals-spurs-illicit-financial-flows [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

African Leadership Magazine (2025). Diaspora bonds: Africa’s new economic lifeline. African Leadership Magazine. Available at: https://www.africanleadershipmagazine.co.uk/diaspora-bonds-africas-new-economic-lifeline/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Arise News (2025). Egypt, Nigeria lead Africa’s remittance inflows with USD 95bn in 2024. Arise TV. Available at: https://www.arise.tv/egypt-nigeria-lead-africas-remittance-inflows-with-95-billion-report-says/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Bank of Botswana (2024). Annual Report 2023. Bank of Botswana. Available at: https://www.bankofbotswana.bw/sites/default/files/publications/2023%20Annual%20Report%20Final.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Botlhale, E.K. (2024). A sovereign wealth fund as an alternative driver of growth and development? The Pula Fund case study. Sovereign Wealth Fund Journal. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21681392.2024.2312183 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Brookings (2022). Diaspora bonds: An innovative source of financing? Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/diaspora-bonds-an-innovative-source-of-financing/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Carnegie Endowment (2024). African strategies to combat illicit financial flows. Carnegie Africa Program. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/11/illicit-financial-flows-africa-tax [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Dabafinance (2025). Top 10 diaspora remittance destinations in Africa. Dabafinance. Available at: https://dabafinance.com/en/insights/top-10-diaspora-remittance-destinations-in-africa [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

EY (2024). EY Africa Attractiveness Report 2024. Ernst & Young. Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_nl/foreign-direct-investment-surveys/why-africa-fdi-landscape-remains-resilient [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Further Africa (2025). Africa’s foreign direct investment surges 75% to record USD 97bn in 2024. Further Africa. Available at: https://furtherafrica.com/2025/06/23/africas-foreign-direct-investment-surges-75-to-record-97-billion-in-2024/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

GFRID (2025). Remittances from African diaspora grew in 2023, set to exceed USD 100bn in 2024. Global Forum on Remittances & Development. Available at: https://gfrid.org/remittances-from-african-diaspora-grew-in-2023-set-to-exceed-100bn-in-2024/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

IFAD (2023). RemitSCOPE Africa Report 2023. International Fund for Agricultural Development. Available at: https://www.ifad.org/en/w/publications/remitscope-africa-report-2023 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

IFSWF (2023). Sovereign Wealth Funds Report 2023. International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds. Available at: https://static.ie.edu/CGC/2023_Sovereign_Wealth_Funds_Report.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

IMF (2023). Botswana: 2023 Article IV Consultation—Press Release. International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2023/317/article-A001-en.xml [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Institute for Security Studies (2025). Remittances as development finance: Africa’s overlooked billions. ISS Today. Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/remittances-as-development-finance-africa-s-overlooked-billions [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

ODI (2025). From remittances to bonds: Mobilising diaspora finance in African economies. Overseas Development Institute. Available at: https://odi.org/en/insights/from-remittances-to-bonds-mobilising-diaspora-finance-in-african-economies/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

ODI (2025). Who holds the biggest foreign investment in Africa? Not China. ODI Insight. Available at: https://odi.org/en/insights/who-holds-the-biggest-foreign-investment-in-africa-not-china/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

OMFIF (2024). Banking on the diaspora. Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum. Available at: https://www.omfif.org/2024/11/banking-on-the-diaspora/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Reuters (2024). Nigeria seeks managers for planned USD 10bn diaspora fund. Reuters News. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigeria-seeks-managers-planned-10-billion-diaspora-fund-2024-04-26/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

The Africa Report (2025). Five things to know about Kenya’s debut diaspora bond. The Africa Report. Available at: https://www.theafricareport.com/387973/five-things-to-know-about-kenyas-debut-diaspora-bond/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

UN OSAA (2024). Reducing remittance costs to Africa: A path to resilient financing & development. United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Africa. Available at: https://www.un.org/osaa/news/reducing-remittance-costs-africa-path-resilient-financing-development [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

UNCTAD (2023). World Investment Report 2023: International investment trends. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Available at: https://unctad.org/publication/world-investment-report-2023 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

UNCTAD (2025). Africa: Foreign investment hit record high in 2024. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Available at: https://unctad.org/news/africa-foreign-investment-hit-record-high-2024 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

UNCTAD & Africa-Europe Foundation (2023). Africa loses USD 88.6bn annually to illicit financial flows. Africa-Europe Foundation Tracker. Available at: https://www.africaeuropefoundation.org/uploads/AEF_Infosheet_AUEU_Tracking_IFFS.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

UNODC (2025). Illicit financial flows and their impact on development. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/iff.html [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

Wilson Center (2025). The innovative landscape of African sovereign wealth funds. Wilson Center Blog. Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/innovative-landscape-african-sovereign-wealth-funds [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].

World Bank (2024). Remittances slowed in 2023, expected to grow faster in 2024. World Bank Press Release. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/06/26/remittances-slowed-in-2023-expected-to-grow-faster-in-2024 [Accessed 30 Aug. 2025].