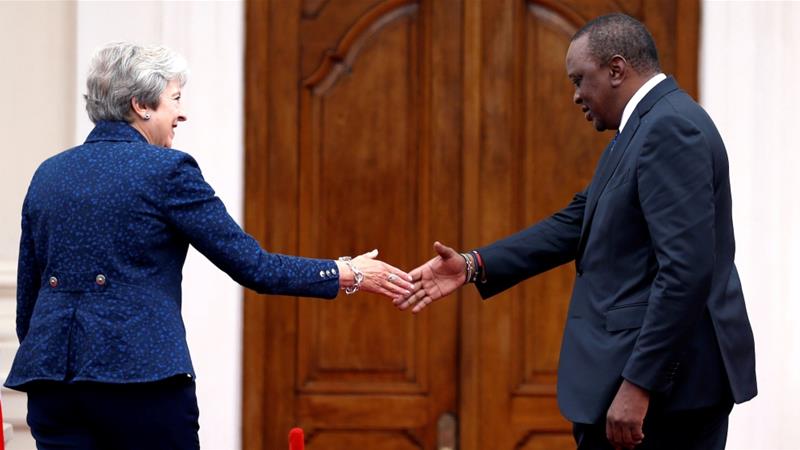

In August 2018, then-Prime Minister Theresa May became the first British leader in five years to visit sub-Saharan Africa, making a three-day trip that included meetings with the presidents of South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya.

May was on the continent to boost post-Brexit trade and convince African leaders that the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union would provide their nations with new and lucrative trade and investment partnerships with the UK.

In a speech in Cape Town, she pledged four billion pounds ($5.3bn) in support for African economies, to create jobs for young people. She also pledged a “fundamental shift” in aid spending to focus on long-term economic and security challenges rather than short-term poverty reduction.

May’s promise to create a “global Britain” that views Africa as a primary trade partner triggered excitement and expectation on the continent. However, her May 2019 resignation and Boris Johnson’s rise to power put the realisation of a stronger relationship between post-Brexit Britain and Africa into question.

Unlike May, Johnson barely showed any interest in Africa, instead focusing his attention solely on convincing the British public that he is the right man to “get Brexit done”.

Nevertheless, African leaders, especially the ones from former British colonies who already have significant trade relations with the UK, doubled down on their efforts to charm Britain into making them primary trade partners after Brexit.

Following Boris Johnson’s stunning electoral victory on December 12, for example, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari swiftly sent him a congratulatory message, wishing the prime minister well and expressing his hopes for stronger ties between Nigeria and the UK.

Ghana’s Nana Akufo-Addo also offered his congratulations to Johnson, saying, “we have an opportunity, together, to renew and strengthen the relations between our two countries, focusing on enhancing trade and investment, and scaling up prosperity for our peoples”.

Buhari and Akufo-Addo’s statements were not empty pleasantries, rather they were expressions of an ever-growing belief across the continent that post-Brexit Britain could provide a quick fix for stagnating African economies.

It is still questionable, however, whether the anticipated new relationship will ever materialise and, perhaps even more importantly, whether Africa will be able to benefit from it if and when it does.

First of all, it is highly unlikely that Johnson is going to give priority to securing new deals with African nations following his country’s imminent exit from the EU. After all, the populist prime minister never embraced his predecessor’s dreams for a “global Britain” and focused instead on building closer ties between London and Washington.

Moreover, many African countries currently have preferential access to the UK because of trade deals hashed out over the years with the European Union, such as Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) and the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative. Following Brexit, it may take considerable time for each nation to replace these with equivalent or better deals, and they may be forced to pay increased tariffs for their exports to the UK in the process.

But even if a new partnership between the UK and African nations does miraculously take shape soon after Britain’s exit from the EU, it will not be easy for a continent weighed down by multiple domestic challenges to make immediate gains.

A significant percentage of any gain African nations may make from a lucrative trade partnership with post-Brexit Britain, for example, will immediately be cancelled out due to their existing debt to the continent’s mega-investor, China. While Chinese debt cannot stop Africa from forming new partnerships, it will indeed make any future deal less profitable.

But beyond the debilitating effects of the Chinese debt-trap Africa is currently in, there are other, and entirely home-grown reasons why Africa will likely not be able to capitalise on Britain’s imminent exit from the EU.

In the recent past, African countries have signed countless cooperation agreements with nations across the world, from the EU to the US and Turkey. Every country in the world, after all, wants a share of Africa’s rich resources. But, despite the plethora of investments, African countries sank ever deeper into poverty. Today, Africa is the world’s second-fastest-growing region, and yet 100 million more Africans live in extreme poverty today compared with the 1990s. Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, is home to the largest share of people living in extreme poverty.

The main reason behind African nations’ inability to reap the rewards of international cooperation and investment is corruption. Cooperation with post-Brexit Britain, therefore, can yield significant dividends for Africans only if African countries clean up their acts on the domestic front.

Most African countries are blessed with huge reserves of precious natural resources as well as young and capable populations. Moreover, they have long been receiving financial support from the international community. While all this could not have reversed all the damage colonialism has done to the continent, under better domestic conditions, it could have triggered an economic boom and carried most African nations out of poverty.

That boom, however, failed to materialise. Elites across the continent chose to line their pockets rather than help elevate their nations. Corruption flourished, and tax revenues and foreign aid were diverted into the bank accounts of the select few while masses were left to fend for themselves with little to no support from their governments.

Read Also: Brazil: Dozens Killed As Heavy Rains Cause Floods

If African leaders want to form a genuinely beneficial partnership with post-Brexit Britain, they need to devise a new approach to fighting corruption. Furthermore, they need to start exercising fiscal prudence and entrenching good governance. As long as the upper echelons of African societies remain rotten, a hike in British investments and trade, however significant it may be, will not help the peoples of Africa.

In 2012, Nigeria was estimated to have lost over $400bn to corruption since independence. In 2018, it was ranked 144 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Perception of Corruption Index. Many other African countries experience similarly high levels of corruption and bad governance. Equitable development will remain a mirage in such an environment even if these countries were to make a deal with God, not merely with the UK.

It is naive to believe that corrupt African leaders who have led their countries to destitution will allow the benefits from a future UK trade deal trickle down to regular Africans in need and elevate the continent. It is true that Brexit can be an opportunity for Africa, but only if the continent’s leaders finally move away from corruption and start working to help their people rather than themselves.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

AL JAZEERA