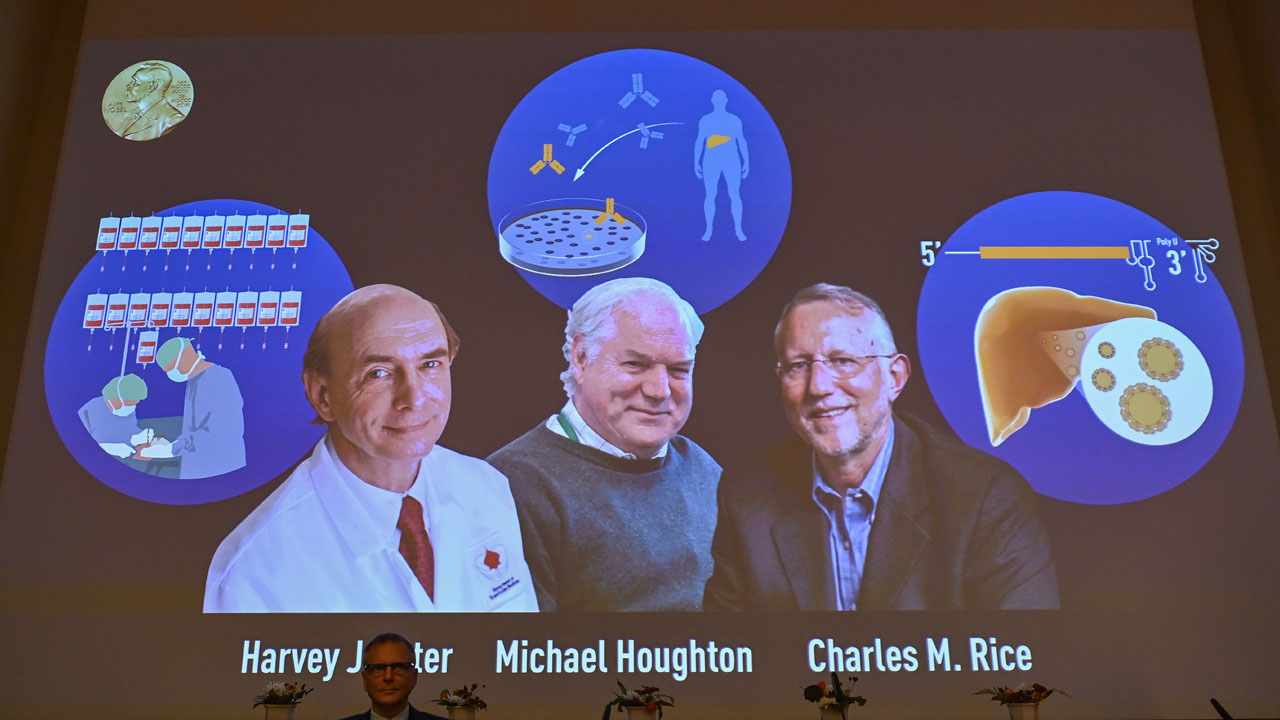

The three were honoured for their “decisive contribution to the fight against blood-borne hepatitis, a major global health problem that causes cirrhosis and liver cancer in people around the world,” the jury said.

The World Health Organization estimates there to be around 70 million Hepatitis C infections globally, causing around 400,000 deaths each year.

Thanks to their discovery, highly sensitive blood tests for the virus are now available and these have “essentially eliminated post-transfusion hepatitis in many parts of the world, greatly improving global health”, the Nobel committee said.

Their discovery also allowed the rapid development of antiviral drugs directed at Hepatitis C.

“For the first time in history, the disease can now be cured, raising hopes of eradicating Hepatitis C virus from the world population,” the jury said.

Prior to the trio’s work, the discovery of the Hepatitis A and B viruses had seen critical steps forward, but the majority of blood-borne hepatitis cases remained unexplained.

“The discovery of Hepatitis C virus revealed the cause of the remaining cases of chronic hepatitis and made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives,” the jury said.

Alter was credited for his pioneering work studying the occurrence of hepatitis in patients who had received blood transfusions, determining that their illness was neither Hepatitis A or B.

Houghton built on Alter’s work to isolate the genetic sequence of the new virus.

Rice subsequently completed the puzzle by using genetic engineering to prove that it was the new strain alone — Hepatitis C — that was causing patients to get sick.

The trio will share the Nobel prize sum of 10 million Swedish kronor (about $1.1 million, 950,000 euros).

They would normally receive their prize from King Carl XVI Gustaf at a formal ceremony in Stockholm on December 10, the anniversary of the 1896 death of scientist Alfred Nobel who created the prizes in his last will and testament.

But the in-person ceremony has been cancelled this year due to the coronavirus pandemic, replaced with a televised ceremony showing the laureates receiving their awards in their home countries.

– Pandemic effect on prizes? –

The award for work on a virus comes as the world battles the new coronavirus pandemic, which has put the global spotlight on science and research.

“The pandemic is a big crisis for mankind, but it illustrates how important science is,” Nobel Foundation head Lars Heikensten said.

However, no prizes were expected to be awarded this year for work directly linked to the new coronavirus, as Nobel prize-winning research usually takes many years to be verified.

The prize-awarding committees are “not in any way influenced by what is happening in the world at the time,” Erling Norrby, the former permanent secretary of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences which awards the science prizes, told AFP.

“It takes time before a prize can mature, I would say at least 10 years before you can fully understand the impact” of a discovery, Norrby, himself a virologist, said.

The work of the various prize committees is shrouded in secrecy and the names of the nominees are not disclosed for 50 years, leading to rampant speculation.

The winners of this year’s physics prize will be revealed on Tuesday, with astrophysicists Shep Doeleman of the US and Germany’s Heino Falcke seen as possible winners for work that led to the first directly observed image of a black hole in April 2019.

American mathematician Peter Shor who paved the way for today’s research on quantum computers, or France’s Alain Aspect for his work on quantum entanglement, have also been mentioned in Swedish media.

The chemistry prize announcement will follow on Wednesday, followed by the literature prize on Thursday.

Speculation ahead of Friday’s peace prize has meanwhile focused on press freedom groups, Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg and other climate activists, or several UN organisations.

The economics prize will wrap up the Nobel prize season on Monday, October 12.

AFP